Original article: Maricunga: no es llegar y llevar, los flamencos gritan el costo ecológico del litio

In the high Andean mountains of Atacama, where water is a precious resource, the Maricunga salt flat is becoming synonymous with economic prospects. However, for the ecosystem, the future is not determined by presentations—it hinges on water millimeters, fragile wetlands, and reproductive cycles that rely on the wetland remaining intact. Here, the flamingos—with their nests, colonies, and chicks—are not merely part of the scenery; they serve as a warning signal.

The government has updated the Special Lithium Operating Contract (CEOL) to greenlight the project at the Maricunga Salt Flat, currently driven by Codelco in partnership with Rio Tinto. According to state reports, the modification expands the area covered, adjusts timelines, and includes contributions for nearby communities after a consultation process that has been criticized by some indigenous groups.

The official narrative frequently uses terms like “sustainability,” “governance,” and “shared value.” However, it is essential to note that promises do not change the realities of the desert. The publicly disseminated roadmap outlines an initial phase of lithium carbonate production starting in 2030, using evaporation methods; followed by a second phase starting in 2033 that aims for direct extraction technologies (DLE). In simpler terms: the plan kicks off with the method that demands the most water and then promises improvements.

Ecological Cost of Lithium in Maricunga: Water That Sustains Life

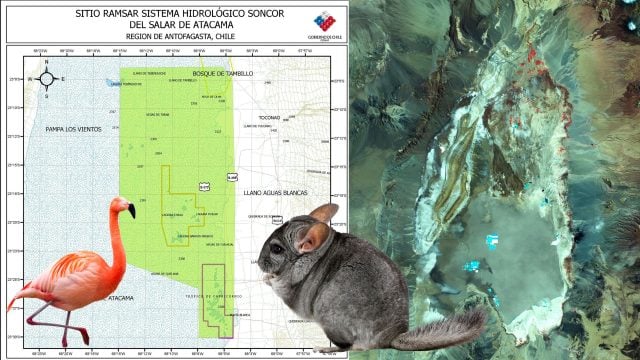

The most uncomfortable ecological evidence is abundant—both visually and in the counts. CONAF reported the presence of 1,248 Andean and Chilean flamingos in the Great Lagoon of Maricunga, along with a colony of 253 James flamingos nesting with hatching chicks. This monitoring, carried out by park rangers, reinforces that this is not just any map location; it is one of the most significant areas for flamingo concentration and nesting in the country.

Adding to this evidence, another recent finding emerged: on January 26, Fundación Symbiótica revealed through Ladera Sur a recording of a colony of nearly 2,000 flamingos in Maricunga. More than just a number, this serves as an ecological alert: the salt flat acts as a biological refuge in a geography where water cannot be taken for granted.

Another alarming fact should trouble any authority speaking of “protection”: CONAF warns that not all of the Maricunga Salt Flat is under official protection, leaving a significant area of lagoons without that coverage, including the Great Lagoon. Furthermore, it’s important to remember that in 2023, there was a reproductive success of over 800 Andean flamingos. This means the ecosystem is active, reproducing, and functioning. It is not a “productive void” waiting for mining.

Ecological Cost of Lithium in Maricunga: Scientific Alerts and the Atacama Precedent

If anyone believes that «it will be different here» by decree, it is wise to examine the closest precedent: the Atacama Salt Flat, where lithium has been mined for decades and the environmental debate remains open. A study published in Proceedings of the Royal Society B (based on 30 years of data) concluded that at a regional scale, the abundance of flamingos fluctuates significantly based on water levels and productivity; and that, locally in the Atacama Salt Flat, lithium mining is negatively correlated with the abundance of two out of three species evaluated. The authors warn that increased mining paired with diminished surface water could lead to dramatic effects.

This is not just an “academic discussion.” In September 2025, the Superintendence of the Environment fined Albemarle—one of the largest lithium producers globally—for excessive brine extraction: according to the SMA, the average annual flow extracted during the operational year 2019–2020 surpassed authorized limits. Additionally, there were violations of their Early Warning Plan (PAT), which included failing to notify the activation of an indicator and not immediately reducing extractions in February and March 2021. In other words: when the system signaled «danger,» the brakes were not applied as they should have been.

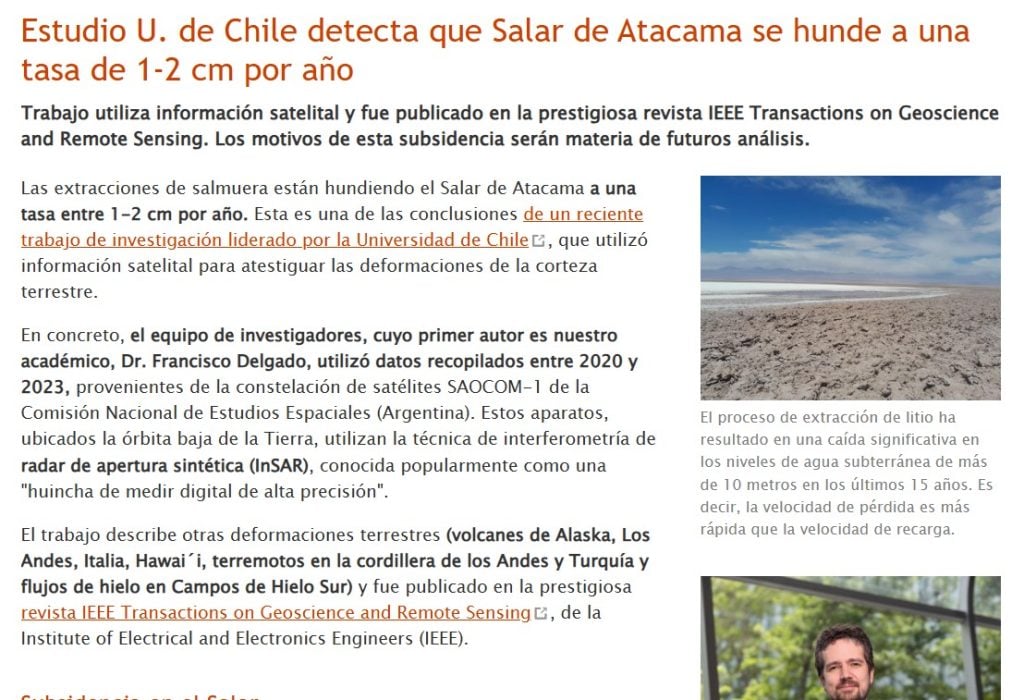

Moreover, a geophysical alert straight out of science fiction, but indeed very real: a study from the University of Chile reported detected subsidence (sinking) in sections of the Atacama Salt Flat—1 to 2 cm per year—connected to brine extraction at a rate exceeding natural recharge. It underscores a critical point for the Maricunga debate: «Lithium is obtained through evaporation, a process that causes 90% of the water to be lost to the atmosphere.»

Blind Spots: Data, Oversight, and Inescapable Questions

The underlying problem is not merely technological. It is political and rooted in information. A 2023 paper on the socio-environmental debate of lithium in Atacama describes a “disbalanced” field of knowledge in which information production may be incomplete and the roles of different actors remain under tension. When critical data is concentrated, oversight weakens, and public trust erodes.

There is also an additional blind spot: how brine is accounted for and what is understood as “water” in these systems. A 2025 study in Water (MDPI) reviews controversies regarding the classification and “accounting” of brines in the Atacama Salt Flat, showing that even technical frameworks have foundational disputes. Another research piece from the same year investigates how to incorporate localized impacts (groundwater levels, lagoons, brine–freshwater mixing, feedback mechanisms) into “localized” water footprints. If the measurement method is under dispute, the risks are clear: significant decisions are made based on weak rules.

Thus, before promoting Maricunga as the “second engine” for lithium, there are questions that cannot remain unanswered: what will be the complete and publicly available baseline for water and ecology? What thresholds will trigger real, enforceable brakes with proportional penalties? Who will monitor—and with what independence—when the plan starts with evaporation? How will areas not yet under official protection be safeguarded?

Ultimately, Maricunga is not just about seizing resources. If the flamingos are “screaming” anything, it is not poetry; it is biology. The ecological cost of lithium in Maricunga cannot be measured solely in tons or announcements; it is quantified by the missing water, changing wetlands, and the state—and society’s—capacity to impose boundaries before the Atacama salt flat precedent is no longer a warning but a repeated script.