Original article: Karina Delfino recuerda la chispa que encendió la «Revolución Pingüina»: «¿Por qué si no tengo dinero estoy condenada?»

«The quality of education was at risk because it depended on whether you had financial resources or not,» pointed out the former spokesperson of the «Penguin Revolution» in a BBC podcast.

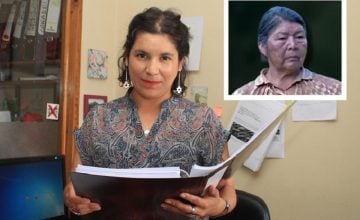

In 2006, Chile experienced an unprecedented social upheaval. Over 600,000 high school students, dressed in navy blue and white uniforms, left their classrooms and took to the streets in a massive protest challenging the foundations of the educational system inherited from Augusto Pinochet’s dictatorship (1973-1990). This movement, known as the «Penguin Revolution,» not only marked a turning point in Chile’s recent history but also forged a new generation of leaders. Among them was a 16-year-old, Karina Delfino Mussa, who, from her position in Quinta Normal, rekindled the spark that ignited this social phenomenon in a BBC interview.

The Awakening of a Generation: «Why Am I Condemned If I Have No Money?»

Journalist Grace Livingstone, in her BBC podcast «Witness History,» captured the atmosphere of those days: «There was a sense of change in the air, a desire for social transformation,» while Karina Delfino, then president of her high school’s student council, described the environment within the student movement: «There was a sense of change in the air, a desire for social transformation. I would say it was a kind of (…) I don’t want to say chaotic, but a type of ecstasy in terms of the mobilization and paralysis of all the schools,» recounted the sociologist.

The movement highlighted the structural inequality that was latent in the country.

“It was the parents’ ability to pay that ultimately determined the opportunities for their children. This was what was raised for the discussion of the Penguin Revolution,” explained Delfino, remembered as the spokesperson of the movement.

She noted that the protests occurring between April and June 2006, reactivated in September and October of the same year, with over 100 schools paralyzed, constituted a mass organic response to decades of an educational system designed during Pinochet’s dictatorship that turned education into a market commodity.

The Constitutional Organic Law on Education (LOCE), enacted in 1990, had institutionalized a model where “the capacity of parents to pay ultimately determined their children’s opportunities,” Delfino explained.

In this context, she referred to the question that resonated on every banner: «Why is it that if I don’t have money, I’m almost condemned to not being able to attend university?»

“The quality of education was at risk because, ultimately, educational inequity depended on whether you had financial resources or not,” she pointed out.

Karina’s social awareness grew during her experiences in a humble neighborhood in Santiago: «I grew up with a lot of love, but material things were not abundant. For example, there were Christmases when it was difficult for my mother to prepare any food,» she recalled.

In her elementary school, she witnessed the harshness of neglect: «Sometimes, the classroom windows would break, or the bathrooms didn’t work. We lacked materials such as pencils or erasers, but the teachers were very committed.»

At 15, while being president of her student center, she began connecting with leaders from other schools. All diagnosed the same issue: the legacy of dictatorship. Determined to understand the legal mechanisms that perpetuated inequality, she immersed herself in an unusual study for a teenager. «I started studying. Imagine how furious my mom was, while my friends were studying math and languages, I was studying educational law. The laws and finances,» recounted the socialist militant.

From Street Protest to Peaceful Takeover

Mobilizations began to grow starting in April 2006, with emblematic cases like the Carlos Cousiño High School in Lota, whose classrooms would flood every winter. However, an episode of violence during a large demonstration in Santiago in early May led student leaders, including Delfino, to reconsider their strategy.

«There were always infiltrated police. They always mingled with the people who infiltrated the march. They damaged traffic lights, bus stops, and electric signs. And because they damaged things, the media only reported negative news,» recalled the current mayor.

«So we said, let’s change the strategy. We will occupy our schools because if we occupy our schools peacefully, the media won’t be able to show any destruction and will report what we want to say,» she emphasized in the BBC podcast.

With that determination, in the early morning of May 19, 2006, they executed the plan.

«We took the first school, called Liceo de Aplicación. The police arrived with municipal officials because we occupied it at 2 a.m. But just when the police arrived there, the students began to occupy the Instituto Nacional, which is one of the most well-known schools in Chile. Then the third school was occupied,» she commented.

By 7 in the morning, three emblematic institutions were in the hands of the students. The news spread like wildfire. «

In the following weeks, students across the country began to occupy their schools,» Delfino narrated, making it clear that the occupations were not acts of vandalism, but acts of care and reclamation.

«I went to many occupied schools to say the same thing, that there would be no damage to the schools. On the contrary, we would repair them and that’s what we did, we painted murals,» she pointed out.

What Do These Students Want?: When Public Opinion Could No Longer Ignore Them

The strategy worked. The media, drawn by the novelty of organized, peaceful occupations, turned their microphones and cameras toward the youth. «So the press started asking us, what do these students want? They started interviewing us,» said the current mayor.

The crucial moment arrived at 5 a.m. on May 30, 2006. A journalist called Karina to inform her that students had taken over a high school in Easter Island, a Chilean island territory in the middle of the Pacific.

«This meant that every region of Chile had an occupied school,» the journalist Grace Livingstone emphasized, highlighting that they understood the mobilization was complete.

«When the president of the Republic [Ricardo Lagos] spoke about the students’ mobilization, he created a moment, a kind of ‘click,’ in which the political system realized us and understood that they had to take us into account,» analyzed the sociologist.

The pressure was so great that the Lagos government quickly agreed to several short-term demands: it approved funds to repair deteriorated schools, eliminated fees for taking the Academic Aptitude Test (PSU) for 80% of the most vulnerable students, and established free school passes permanently.

A Legacy of Struggle and Pending Reforms

The movement forced a constitutional debate on education. Although the LOCE was repealed in 2009 and the General Education Law (LGE) was enacted, many activists considered that the new regulations did not address the root of the problem by maintaining profit-making subsidized private schools.

Nonetheless, the Penguin Revolution planted an undeniable seed, as it directly inspired the massive student protests of 2011 and laid the groundwork for educational reforms pushed during Michelle Bachelet’s second government (2014-2018).

These reforms, deemed historic, prohibited profit-making in schools receiving public funds and established free higher education for the 60% of the country’s least affluent students.

For Karina Delfino, now working in municipal management in Quinta Normal, the fight continues.

«It is essential that quality education is provided to all children, regardless of their birthplace, their background, or their family’s resources,» she asserted, with the same conviction she had at 16.

«So just because they were born in a certain area or attended a particular school, that doesn’t mean they can’t progress,» she pointed out.

Almost 18 years ago, the Penguin Revolution demonstrated that the demand for social rights, when organized and persistent, can shift the course of history. Karina Delfino’s testimony serves as living proof that the seeds planted in 2006, amid occupations, banners, and a fervent desire for justice, continue to bear fruit in building a more equitable Chile.

You can listen to the BBC podcast where Karina Delfino was interviewed through this LINK