Original article: Estados Unidos: De la república antimilitarista al Estado armado y criminal

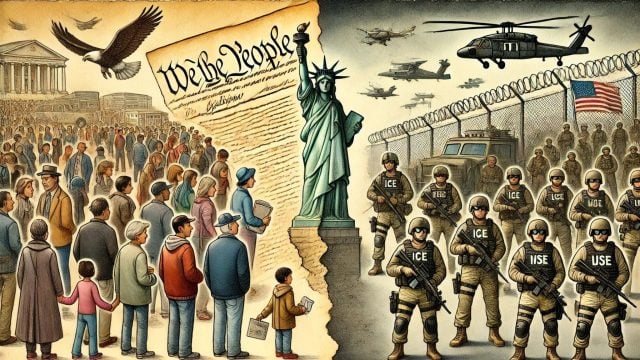

In its origins, the United States was envisioned as a deeply antimilitarist republic. The colonial experience under British rule left a clear imprint, as permanent armies were viewed as tools of oppression rather than guardians of freedom. However, more than two centuries later, the country showcases one of the largest military and domestic security apparatuses in the world, both abroad and within its borders. This stark contrast is hard to ignore, and we will reflect on how, since its inception, this trajectory has reached a point that could signify the end of its cycle.

By Bruno Sommer

The Past: A Constitution Against Militarism

The U.S. Constitution explicitly reflects this foundational fear. The so-called Founding Fathers crafted a system where military power was strictly subordinated to civilian authority. Congress—not the Executive—holds the power to declare war; military funding must be renewed periodically; and the notion of a standing army has always been a topic of debate and suspicion.

James Madison warned that professional armies were “instruments of tyranny.” Thomas Jefferson advocated for small, temporary, defensive forces. Even George Washington cautioned in his farewell address about the dangers of unchecked military power and permanent alliances.

The Second Amendment, now reinterpreted almost exclusively as an individual right to bear arms, was born in this context, intended for citizen militias as a counterbalance to centralized military power, not as a celebration of state armament. This amendment has also led to tragedies involving innocent citizens in a country that has yet to grasp that guns “are carried by the devil” and wielded by those who refuse to reason.

The External Present: The Military Hyperpower

This original design stands in stark contrast to today’s reality. The United States currently maintains hundreds of military bases overseas, with a permanent armed presence in multiple regions worldwide, backed by a war and defense budget that far exceeds that of any other nation.

Since World War II, and especially during the Cold War, the country has transitioned into a structurally permanent militarization, normalized and legitimized by the idea of global security. President Dwight D. Eisenhower himself warned in 1961 about the dangers of the military-industrial complex, a caution that has proven prophetic over time.

“In the councils of government, we must guard against the acquisition of unwarranted influence, whether sought or unsought, by the military-industrial complex. The potential for the disastrous rise of misplaced power exists and will persist. We must never let the weight of this combination endanger our liberties or democratic processes. Only an alert and knowledgeable citizenry can compel the proper meshing of the huge industrial and military machinery of defense with our peaceful methods and goals, so that security and liberty may prosper together.”

“En los consejos del gobierno, debemos protegernos contra la adquisición de una influencia injustificada, buscada o no, por el complejo militar-industrial. El potencial para el surgimiento desastroso de un poder mal ubicado existe y persistirá. Nunca debemos permitir que el peso de esta combinación ponga en peligro nuestras libertades o los procesos democráticos. Solo una ciudadanía alerta y bien informada puede lograr que la enorme maquinaria industrial y militar de defensa se integre adecuadamente con nuestros métodos y objetivos pacíficos, de modo que la seguridad y la libertad prosperen juntas.”

Nevertheless, war has ceased to be an exception and has become a latent condition of U.S. foreign policy, backed by opaque legal resources and companies dedicated to it, like Palantir.

The Internal Present: The Militarization of Security

The shift, however, is not only external. Domestically, agencies like ICE (Immigration and Customs Enforcement) symbolize a profound transformation of the state. Established after 9/11 under the logic of “national security,” ICE operates with quasi-military structures, extensive detention powers, and armed operations within civilian communities.

Border control, migration, and internal order have increasingly been treated as military matters rather than civil ones. This has led to criticism for human rights violations, excessive use of force, and a logic of internal enemies that clashes directly with the original constitutional spirit and could lead to serious confrontations between citizens weary of ICE’s abuses, which have resulted in hundreds of detentions of migrants as well as killings of American citizens due to the anti-immigration policies enacted by the current administration.

The paradox, the contradiction, is evident in a country founded on distrust of permanent armed power, which has transformed into a society where military and police force is a daily element of governance.

Where once the army was feared as a threat to freedom, its presence—both external and internal—has been normalized as a guarantee of order. Where the Constitution aimed to limit the coercive power of the state, the present expands it under the guise of security.

Claiming that the United States was antimilitarist in its origins is not an ideological exaggeration, but a historically grounded assertion. What is more revealing is to realize how far today’s America has strayed from its foundational design, completing a cycle in which the repudiation of its actions arises not only from abroad but also from within, simmering in a pressure cooker.