Original article: Incendios forestales: Tragedia que el Estado sigue tratando como emergencia y no como factor estructural de la política pública

By Sara Larraín, Director of Chile Sustentable

Every summer in Chile, the same script unfolds: uncontrollable wildfires, communities threatened or destroyed, ecosystems ravaged, and a government that responds with a focus on emergencies rather than prevention.

This is not a fatality or an unpredictable phenomenon. It is the result of sustained rising temperatures—global warming has already surpassed 1.5 °C—and a scenario where wildfires have become the most significant impact of climate change, both in Chile and worldwide.

Wildfires are now more devastating than floods and landslides, necessitating a review of public policies concerning risks, safety, land use planning, sustainable forestry development centered on highly combustible species, and even the approach and investments—both public and private—in preventing and combating wildfires.

Chile no longer has the same climate, hydrological configuration, vegetation, or urban layout it did 30 years ago. The continuous rise in temperatures, prolonged droughts, and heatwaves have created a new risk landscape, thoroughly documented by scientists.

Additionally, the lack of planning and chaotic urban expansion have produced vast areas of urban-rural interface where wildfires originate. Yet, we continue to operate with institutional frameworks, urban and land use plans, and agroforestry models designed for a reality that no longer exists.

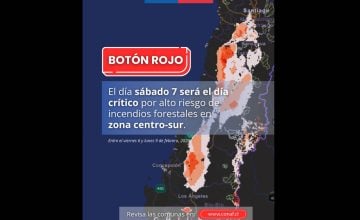

Today, fire is the leading socio-environmental risk in central-southern Chile. It is linked to the urban-rural interface and the absence of prevention, regulation, education, and sanctions, reaching catastrophic magnitudes, especially in areas forested with highly flammable exotic species like pine and eucalyptus.

The mega-fires of the summer of 2016-2017 highlighted this new reality, but ten years later, there is still no coherent, preventative, and binding state policy to address this risk in a structural manner. Responses remain focused on firefighting—including repeated announcements about nighttime operations or aerial reinforcements—despite clear evidence: against mega-fires, firefighting capacities are limited. The key lies in preventing fire ignition and reducing its spread.

This demands concrete territorial actions. Thousands of people today live in high wildfire risk zones, as seen in the town of Santa Olga a decade ago, in Lirquén, and in many other territories currently under threat.

The spread of highly flammable monoculture forests, the lack of effective management plans, the absence of protective strips in the urban-forest interface, and the failure to prioritize the safety of communities and ecosystems in wildfire-prone areas create a foreseen disaster scenario.

Despite shared recognition of this diagnosis, structural transformations in urban development and the forestry sector remain a sensitive topic.

Extensive monocultures of pine and eucalyptus continue for miles without landscape diversification, firebreaks, exclusion areas to protect communities, buffer zones, water tanks, or helipads.

The focus remains on post-fire attack and restoration rather than prevention, even though science indicates precisely the opposite: prevention is more effective, less costly, and socially more equitable.

The few laws in this area presented in recent years, such as the Wildfire and Rural Fire Prevention Bill introduced by the government in September 2023, made swift progress through the Chamber of Deputies and the Senate’s Agriculture Committee.

However, upon reaching the Senate’s Finance Committee, they became stalled. The reason? Pressure from productive sectors arguing that certain measures would hinder private property economic activities.

This legislative blockage is both serious and irresponsible. We cannot continue subordinating people’s safety, ecosystem protection, and climate change adaptation to short-term economic interests. Preventing wildfires is not a barrier to development: it is a basic condition for the security of individuals and for the country’s economic and environmental sustainability.

Chile urgently needs a state policy on wildfires, integrated with the Climate Change Adaptation Plan, focusing on prevention, land use planning, and regional and local participation.

The rising temperatures and other climate conditions brought by global warming exponentially increase the structural risk of wildfires. We have the knowledge and experience, and we must address the deep-rooted causes of the problem.

If the incoming government wants to be consistent with the concept of “emergency” that the elected president’s office has been using, it must begin working today on a Structural Territorial Plan, decisively and urgently sponsor the wildfire prevention bill, and acknowledge that climate and territorial security are also central to national security.

Sara Larraín