Original article: Científico del INACH lleva a Chile a la primera línea en el estudio de microplásticos en la Antártica

Chilean Scientist Pioneers Microplastics Research in Antarctica

Rodolfo Rondón, a researcher at the Chilean Antarctic Institute (INACH), completed a two-month internship at the Marine Environment Laboratory of the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) in Monaco. This experience is crucial for enhancing Chile’s capabilities in microplastics research within Antarctica.

This stay was part of a technical cooperation project between the Chilean government and the international organization, aimed at developing and standardizing advanced methods for detecting and quantifying these particles in various ecosystems on the White Continent.

«This opportunity to travel to Monaco arose from a memorandum of understanding between Chile and the IAEA to implement techniques dedicated to studying microplastic pollution,» INACH representatives explained.

Within this framework, the agency highlighted that a national technical cooperation project was approved, which includes the analysis of microplastics in water, snow, and Antarctic biota, with a focus on key trophic network organisms like krill.

«The goal is to build capacities that enable detailed studies of these particles in the country and position Chile as a reference laboratory at the regional level,» added the Institute.

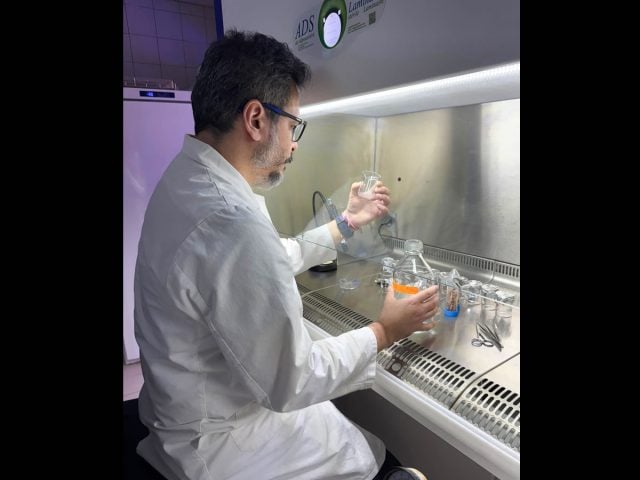

During his time at the IAEA’s Marine Environment Laboratory, the Chilean scientist worked through the complete analysis chain, from receiving and preparing samples to processing them with spectroscopy equipment, all within a meticulously controlled environment to prevent contamination.

Reflecting on his experience, Rodolfo Rondón stated he was «pleasantly surprised by how the entire laboratory operates from the beginning to the end of sample processing. The level of control maintained to prevent contamination up to the moment the machines are used for detecting and quantifying microplastics is remarkable.»

The work also included the adoption of a harmonized and standardized method for detecting microplastics in water, developed at the IAEA laboratory. Additionally, a specific protocol was designed to detect this material in snow, broadening the monitoring to key physical matrices of the Antarctic environment.

One key takeaway for the researcher was related to living organisms: «What I learned most was how to standardize or harmonize protocols to detect microplastics in biota, which in this case was krill, but it could certainly be done for any other type of organism to harmonize a protocol.»

For the krill samples, the preparation process includes freezing and, when transported to Monaco, lyophilization to dry them coldly without altering the present microplastics.

«We freeze these samples until we can process them; ideally, they should remain frozen because it is easier to remove the shell. However, since that wasn’t possible for the transportation to Monaco, we had to lyophilize them, which means drying them in a cold environment,» Rondón elaborated.

Afterward, the specimens undergo a series of chemical and enzymatic digestions to eliminate tissue and shell remnants without losing the microplastics.

In this process, the scientist notes, «the most challenging aspect of standardizing the methodology is ensuring that no tissue or shell remnants are left, as this would interfere with the readings on the equipment.» This required testing various combinations of times and reagents until a stable protocol was achieved.

Post-digestion, the samples are filtered using gold filters, a critical step for them to be analyzed by the LDIR (Laser Direct Infrared), a device from Agilent that automates much of the analysis process.

«The LIDR is a small device, roughly the size of a printer. It detects, quantifies, and characterizes the microplastics in terms of size, weight, shape, and polymer, which is the most interesting part, as it tells us if it’s polypropylene, polyethylene, or polystyrene,» the researcher described.

According to Rondón, the protocols developed in conjunction with the IAEA aim to detect microplastics ranging from 20 to 300 microns, ensuring visibility in equipment like the LDIR.

The scientist highlights that this technology automates the entire procedure, enabling analyses that would typically take a week or two, or even a month, to be completed in just a few hours, significantly reducing analysis times.

Synergies and Regional Outlook

A central element of the project is the synergy between INACH and the Chilean Nuclear Energy Commission (CCHEN), alongside specialized university laboratories in marine toxicology and spectroscopy.

In this context, Rondón clarifies that the LDIR «measures microplastics from 20 to 300 microns,» while CCHEN «has two other devices, namely the Raman, which reads from 1 to 20 microns, and the FTIR, which measures from 300 microns to 5 millimeters. This covers the entire microplastics range.»

«With this synergy, we are among the few countries under the NUTEC Plastics initiative capable of analyzing microplastics from Antarctica,» he added.

Simultaneously, a complementary regional project is underway, coordinating sampling zones, organisms, and biotic matrices to analyze, aiming to generate comparable and useful results for decision-making in the region.

In the medium term, it is expected that the established capacity will enable the country to become a reference laboratory for Antarctic microplastics and support other Latin American nations present in the region, such as Peru, Ecuador, and Colombia, in the coordinated analysis of samples and the generation of regional diagnostics on microplastic pollution in the White Continent.

The Citizen