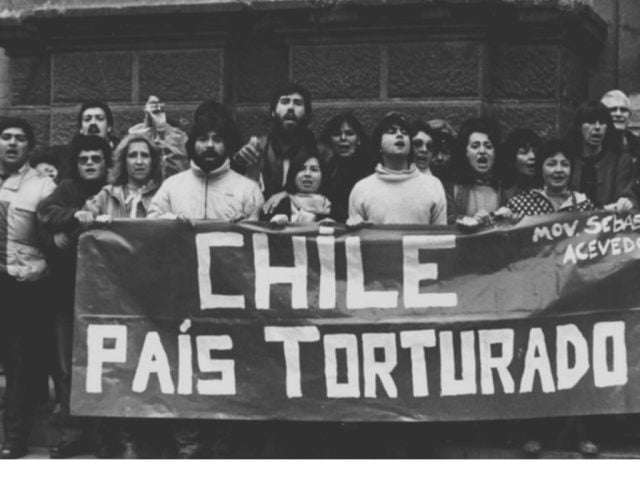

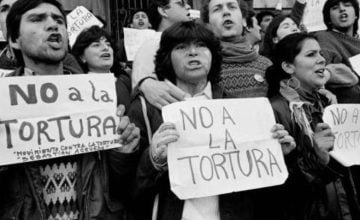

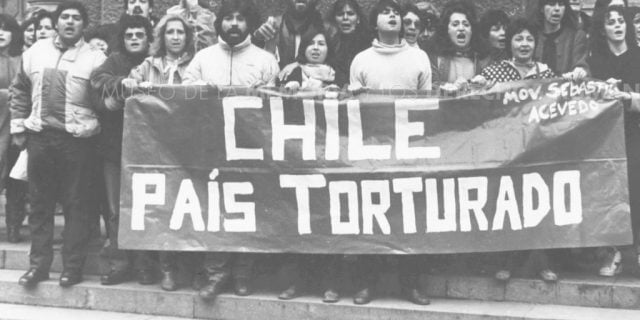

Original article: Militares “lo usaban como piso”: tribunal ordena al Fisco indemnizar a profesor torturado en dictadura

The court ruling emphasizes the testimony of the professor, who indicated that among ‘the cruel abuses he endured and cannot forget’ are the instances when the dictatorship’s prisoners were ‘used as a floor, forced to lie on the ground while the military stood on their bodies to converse.’

The Twenty-Sixth Civil Court of Santiago condemned the Chilean government to pay reparations to a professor who was a victim of political imprisonment, torture, and inhumane treatment at the hands of agents of the civil-military dictatorship.

The judgment issued by Judge Ricardo Cortés Cortés outright dismisses the statute of limitations defense presented by the government, building its decision on a stark narrative of events where the victim’s account of how the military used them ‘as a floor’ stands as a symbol of the systematic degradation that characterized Augusto Pinochet’s regime.

The legal dispute revolved around the government’s claim to declare the indemnification action as time-barred, citing the legal time limits. However, the magistrate determined that the reported acts constitute crimes against humanity, and thus the civil action for reparations is not subject to expiry under civil law.

«The facts that motivate the indemnity action stem from acts constituting crimes against humanity, which means that the non-expiry applies to the civil indemnity action,» the ruling states.

The decision relies on international human rights law and the concept of ius cogens (peremptory norms of general international law). Although it acknowledges that instruments such as the San José Pact or the Rome Statute were not in force at that time, it underscores that norms on crimes against humanity are ‘material sources of international law and cannot be disregarded as they are imperative and generally applicable to the entire international community.’ The judgment adds that temporally restricting victims’ access to justice would make it impossible to fulfill the state’s duty to investigate, sanction, and provide reparations.

This perspective is reinforced by a psychosocial viewpoint. The court cites the ‘Technical Standard for Health Care of Individuals Affected by Political Repression Exercised by the State during the 1973 – 1990 period from the Mental Health Department of the Division of Disease Prevention and Control of Public Health Ministry,’ which states that trauma in victims of crimes against humanity ‘emerges later, transcending even to their relatives, reinforcing that the right to seek reparations from the state for acts committed by state agents during their functions cannot be limited to a timeframe.’

This concept is further supported by a direct quote from UN Rapporteur Theo Van Boven in 1993: ‘It is sufficiently proven that for most victims of gross human rights violations, the passage of time has not erased the scars; quite the contrary, it has led to an increase in post-traumatic stress, requiring all sorts of help and material, medical, psychological, and social assistance for a long time.’

With these arguments, Judge Cortés formally rejected the statute of limitations exception.

The Tale of Horror: From Pozo Almonte to Pisagua

The ruling elaborately details the statement from the plaintiff, F.L.S.D., constructing a narrative of the 21 months of persecution and torment that began when he was detained by Carabineros in Pozo Almonte on December 12, 1973. His torture commenced immediately at the local police station: he was undressed, tied to a chair, beaten ‘cruelly,’ and threatened with having his eyes burned with a cigarette. At night, he was taken to the yard with other prisoners and forced to stand for hours ‘exposed to the desert cold.’

After four days, he was moved to the Telecommunications Regiment in Iquique. There, his confinement in an almost suffocating container was the prelude to torture sessions on the second floor of the building, used by military intelligence. Hooded, he heard conscripts whisper that they apologized for their actions, assuring him they were ‘as scared as he was.’

Tied to a chair, he was beaten with a metal instrument until his ‘face was disfigured’ and he lost teeth. Then came the electricity: ‘They put a headband with wires from his head to various parts of his body, including the testicles and stomach.’ Days later, his body began to bruise.

Professor Tortured and ‘Used as Floor’

Six days after his arrest, the longest chapter of his captivity began: almost nine months in the Political Prisoners’ Concentration Camp of Pisagua.

There, the description reached levels of methodical and humiliating cruelty. The food was ‘intentionally deficient,’ hygienic conditions nonexistent—’the excretions were done in a hole very close to where they consumed the little food they had’—and forced labor was a constant.

However, one particular memory marks the professor’s testimony, where he mentioned that as part of ‘the cruel abuses he endured and cannot forget, were the instances when they were used as a floor, forced to lie on the ground while the military stood on their bodies to converse.’

The psychological suffering deepened as he witnessed the execution of two Communist Party companions ordered by a military council ‘in the same location of Pisagua, in the northern sector, next to the cemetery.’

Finally, on September 14, 1974, he was released without charges, able to resume his role as an educator.

However, the nightmare was not over. Approximately a year later, in August 1975, he was once again detained by military intelligence on false accusations of trying to ‘poison the students’ milk’ and plotting to overthrow the government.

Thus, he spent 23 days in the Dolores Regiment of Santiago, ‘under the same protocol as before, interrogations accompanied by beatings and other tortures,’ only to be relegated in Pozo Almonte, where he was forced to work as a teacher in the rural school there.

The ruling reaffirms the enduring obligation of the Chilean state to respond civilly for the crimes against humanity committed during the dictatorship, asserting that the passage of time does not dilute its responsibility.