Original article: Noticias falsas sobre ejecuciones de adolescentes por ver «El Juego del Calamar» en Corea del Norte: Lo que reveló la verificación

Debunking False Claims of Teen Executions in North Korea Over ‘Squid Game’: Insights from Verification Reports

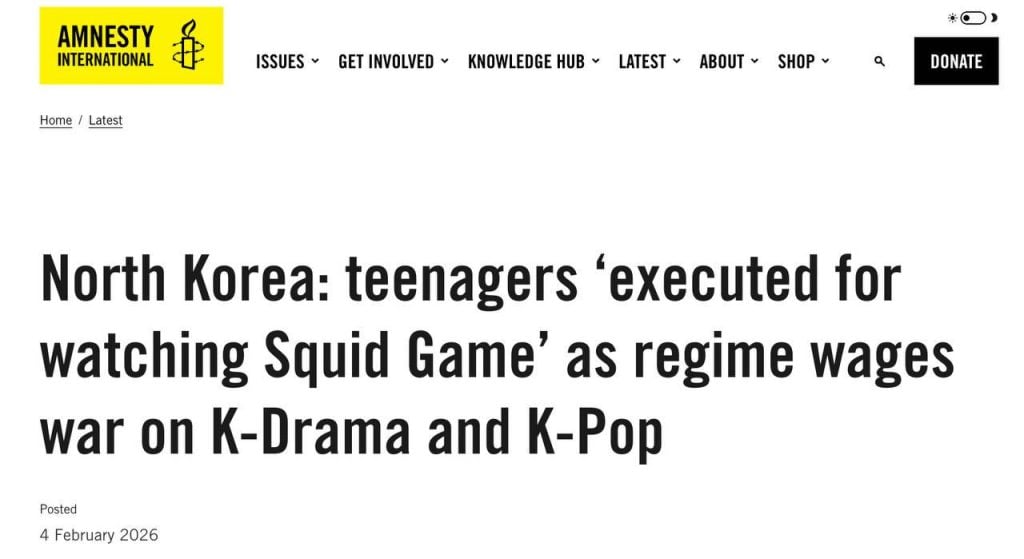

The news that emerged on February 4, 2026, claiming the execution of school students in North Korea for watching the Netflix hit «Squid Game» quickly went viral.

Citing a report from Amnesty International, the message spread rapidly across various media and social networks. The wording of these posts emphasized the stark contrast between the popular series and reports of brutal punishments.

However, if one sets aside the emotional response and examines the actual text of the report—rather than its sensationalized versions—a critical question arises regarding the timeline of the described events.

Amnesty International honestly states in its methodology that its data is based on interviews with individuals who escaped North Korea. At this point, it is crucial to highlight a clear limitation: all interviewed individuals left the country before June 2020.

This is where the facts come into conflict. The global premiere of «Squid Game» occurred in September 2021. Thus, according to the report itself, the interviews were conducted with people who fled North Korea prior to June 2020, while the series premiered in September 2021.

This chronological inconsistency refutes the sensational claim regarding executions found in the coverage of Amnesty International’s material.

Additionally, within Amnesty International’s report, the assertions are accompanied by caveats such as «according to witnesses» and «based on interviews.» However, in media publications, these nuances are often omitted, leading to a more categorical tone. As a result, probabilistic assessments are perceived as established facts.

In this context, reports from the UN and academic studies document restrictions on the consumption of foreign content and instances of public executions in North Korea overall. However, the specific link of «teenagers + specific series + death penalty» lacks documented cases.

To clarify how severe the punishment for such actions truly is in the DPRK, we contacted North Korea expert Andrei Lankov, a candidate for Historical Sciences and a professor at Kookmin University in Seoul, who confirmed that after 2015, both the country’s legislation and law enforcement practices became stricter. However, he has never found evidence of executions simply for viewing videos:

«The new law does indeed specify the death penalty for the distribution of hostile propaganda. However, merely watching does not fall into this category and does not merit capital punishment, not even theoretically,» explained Andrei Lankov.

«In practice, until around 2015, the authorities turned a blind eye to the distribution of South Korean video and audio materials, and since that year, one can be imprisoned for distributing and copying such content. However, I am not aware of a single credible case where individuals have been executed for this,» emphasized the expert.

Unconfirmed Previous Reports of Executions in North Korea

Limited access to information from North Korea complicates independent verification of such reports. Given the scarcity of confirmed data, sensational claims about severe measures often spread widely in the media.

In various instances, reports have emerged regarding the executions of North Korean officials or cultural figures that were later not confirmed.

A classic example is the story of singer Hyon Song-wol. In 2013, authorized global publications, citing the South Korean newspaper Chosun Ilbo, reported on her public execution. The woman, dubbed the «lover» of Kim Jong Un, was reportedly gunned down in front of her fellow musicians.

However, a year later, the «executed» Hyon Song-wol appeared on state television. Furthermore, her career continued to flourish: in 2017, she received a position on the Central Committee of the Party.

The Horror Story Industry: Specifics of Defector Testimonies

Why do these testimonies keep appearing and replicating?

The issue lies in the nature of the sources. The only window into the «black box» of the DPRK are the stories of individuals who have escaped the country.

However, this is a specific type of data that cannot be taken as absolute truth without cross-verification. Moreover, the testimonies of those who have left the country can be used in an information-political context, resulting in an especially thorough need for verification.

Several factors can influence the reliability of such stories:

- Mind Games. Many refugees have experienced severe stress. The psychology of memory is such that, over time, personal experience can merge with heard rumors, forming false memories.

- The Information Market. South Korea officially pays for valuable information about the DPRK. Researcher Jiyoung Song points to a direct correlation: the more sensational the story, the higher the fee. This creates a dangerous incentive for exaggeration.

This information has also been confirmed by expert Andrei Lankov, who states that most of those who escape the DPRK are women, approximately 15% of whom have higher or specialized secondary education.

Yet, even for the most educated North Koreans, adjusting to a different society is challenging, so the monetary reward is not the only benefit they seek.

«It’s not just about the money. Invitations come in, travel happens, useful connections emerge that can transform into employment. Mainly, the people telling these stories are middle class, who are very few among those who have exited the DPRK. But precisely because they are educated and articulate, they understand what «buttons» to press to maximize benefits,» Lankov pointed out.

Adding to this is the demand from the media: journalists seek drama. A story about bureaucratic hardships does not interest anyone, unlike an account of executions. According to Andrei Lankov, it is the sustained demand for shocking content that creates fertile ground for the emergence and dissemination of unreliable testimonies.

«The hot sensations about the DPRK are exactly the kind of stories that Western and South Korean readers want to hear. For example, in South Korea, no one buys the biography of someone in prison for a criminal offense in North Korea, even if it’s unjust. But if they invent a story about being in the most terrible camp from which no one emerged alive, but they did… and describe it in completely fantastic and delirious ways, naturally, people start to read and cite this book,» the specialist asserts.

One widely discussed case that underscores the need for thorough verification of this data is the bestseller «Escape from Camp 14» by Shin Dong-hyuk.

His memoirs about being born in a concentration camp shocked the world, but later, under pressure from inconsistencies, he was forced to admit that a significant portion of the book regarding the cruelty in the DPRK was fabricated.

In this context, South Korean lawyer Jang Kyung-wook openly states that intelligence services and media often use refugees as propaganda tools, without regard for the accuracy of the details.

A.B. Abrams, author of «Atrocity Fabrication and Its Consequences: How Fake News Shapes World Order» and «Surviving the Unipolar Era: North Korea’s 35-Year Standoff with the United States,» notes similar patterns with other prominent figures among the defector community who adapt their stories for a Western audience.

«The famous defector Park Yeon-mi repeatedly claimed she saw ‘how they publicly executed my friend’s mother. Her crime: watching a Hollywood movie,’ something even the harshest critics of North Korea with some knowledge of the country have dismissed as ridiculous,» Abrams points out.

The Logic of Demonization

To understand why these narratives persist despite being frequently debunked, we turn to A.B. Abrams for further comments. He asserts that linking North Korea with a pop culture phenomenon like «Squid Game» is not accidental, but rather a calculated move to reinforce a geopolitical narrative.

«The use of ‘Squid Game,’ a highly acclaimed production from South Korea, in the latest atrocity narrative serves to imply a contrast between the success of a Westernized state and the depravity and massacre in its non-Westernized neighbor,» explained Abrams.

According to the expert, this fits into a broader pattern where Western representations of the DPRK must remain exceptionally negative to sustain the «dominant Western metanarrative.»

Thus, the analysis of cases like «Squid Game» shows a recurring structure: the initial source is an anonymous testimony or story from a DPRK defector; next, the information receives institutional legitimacy through human rights or investigative structures; after that, a broad media echo forms, during which the original caveats gradually disappear.

Moreover, according to expert Andrei Lankov’s observations, right-wing political groups often participate in replicating such sensations, even attracting the attention of human rights organizations like Amnesty International.

«Human rights organizations are often used as weapons in political struggles. Although the human rights defenders themselves may not always realize this, they are willing to attack any authoritarian regime, viewing them as sources of ‘global evil.’ At the same time, they sometimes overlook obvious inconsistencies under the principle of ‘right in principle’ and neglect such important work as fact-checking. And this is not even always specifically targeted against North Korea,» noted Lankov.

The Cost of Unverified Sensations

The story involving Amnesty International’s report and the mention of «Squid Game» has sparked a debate over information verification standards in the realm of human rights. These stories easily root themselves in the information space precisely because they align with the existing image of the country. Under such conditions, critical verification of sources assumes special importance.

Using unverified or controversial claims in such materials can affect the perception of both the subject itself and the organizations raising the issue.

The media often focuses on eye-catching headlines, while the debate on social media amplifies the impact. Simultaneously, later clarifications or corrections generally receive significantly less public attention, affecting the overall informational balance.

Recurring cases of discrepancies in data about the DPRK can diminish public trust in similar reports. In conditions of limited access to information, the transparency of methodology and the precision of wording are particularly important.

The Citizen