Original article: Proyectos extractivos de litio en Chile y su afectación a sitios RAMSAR

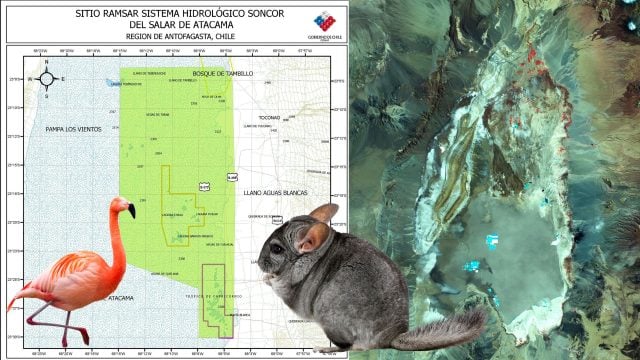

The lagoons and salt flats of northern Chile are not just desert mirrors; they represent fragile ecosystems of immense ecological, cultural, and hydrological value. At the center of this unique landscape lies the Soncor Hydrological System, designated a Ramsar Site since 1996 for its biodiversity and vital ecological function amid one of the planet’s most extreme deserts.

This protection has been framed within the National Lithium Strategy announced in 2023, which has established the commitment to delineate protected areas where extractive operations will not occur, thus aiming to safeguard 30% of ecosystems by 2030.

These areas hold invaluable importance for the life of the communities and species that exist there, which the outgoing government seeks to protect, while the industry views it as a threat to its interests.

El Ciudadano

A Threatened Oasis of Life

The Soncor Hydrological System, located in the Atacama salt flat basin, hosts lagoons like Puilar, Chaxa, and Barros Negros, which sustain iconic birds such as the Andean flamingo (Phoenicoparrus andinus) and James’ flamingo (Phoenicoparrus jamesi), alongside numerous migratory bird species and ecologically significant terrestrial fauna like the Chinchilla.

These wetlands are not only crucial for biodiversity but also represent cultural and hydric capital for the indigenous and pastoral communities that have inhabited this region for centuries.

The Lithium Paradox: «Green Mineral» with Real Environmental Costs

Lithium has been globally promoted as a key mineral for the clean energy transition, essential for electric vehicle batteries and renewable storage. However, this narrative obscures a substantial environmental cost in ecosystems like the Andean salt flats.

In the case of Chile— the world’s second-largest lithium producer—extraction is primarily conducted through the evaporation of lithium-rich brines in large open-air pools. This process intensively extracts both groundwater and surface water, creating cumulative impacts on the water balance of the Atacama salt flat and its associated wetlands.

Independent research and impact analyses warn that the reduction of water reserves, alteration of aquifers, and potential salinization of nearby water bodies are direct consequences of such mining.

Observed Consequences in Ramsar Wetlands

- Decline and fluctuation in water levels in lagoons fed by aquifers interacting with the brine system, putting at risk the reproduction and survival of sensitive waterfowl.

- Decrease in populations of Andean and James’ flamingos, emblematic species of the region, linked to the intensive extraction of groundwater.

- Disruption of water sources for local communities and traditional activities, such as camelid husbandry and high-altitude agriculture.

Environmental organizations have even alerted the Ramsar Convention Secretariat that the exploitation of lithium and other minerals is jeopardizing several Ramsar-designated sites in Chile, including the Atacama, Maricunga, and Surire salt flats.

Policies and Local Political Tensions

In response to these threats, the Chilean government has advanced the creation of a Protected Salt Flats Network, which aims to safeguard over 510,000 hectares of salt flats and high-altitude wetlands through environmental protection designations. This network includes various indigenous consultation processes, recently completed for some key territories.

However, the strategy has generated conflicts with the lithium industry and business actors who press for maintaining and expanding mining concessions even within areas of declared or proposed environmental value.

Experts indicate that if the energy transition relies on lithium extracted from fragile ecosystems like the high Andean salt flats without rigorous environmental assessment and community consultation, we will be swapping one environmental crisis for another.

This is not just a problem for Chile. Throughout the Lithium Triangle (Chile, Argentina, and Bolivia), unique salt flats are at risk due to the extractivist logic that prioritizes production over ecological conservation and social justice.

Action Proposal

As a society and international community, we must:

- Demand independent, cumulative, and long-term environmental assessments before authorizing new extractive projects.

- Strengthen protective mechanisms for Ramsar wetlands against economic pressures.

- Fully respect the rights of indigenous peoples and local communities in decisions affecting their territories.

- Promote cleaner extraction technologies and circular lithium economies, reducing dependence on destructive methods.

- a. Require cumulative and transparent EIAs

- Mandate cumulative environmental assessments for any new project or expansion in saline basins that feed Ramsar wetlands, with standardized hydrological methods and open data. (One EIA per project is insufficient; effects must be summed).

- b. Long-term independent hydrological monitoring

- Piezometric and meteorological stations with real-time public data, managed by an independent entity (public university + CONAF/environmental authority), with quarterly public reports.

- c. Restriction zones—prohibit extraction in areas with direct hydraulic connectivity to Ramsar wetlands

- Establish buffers and prohibitions on new wells within the hydrological influence zone of the Ramsar wetlands that comprise the Soncor hydrological system. (This is compatible with the Protected Salt Flats Network promoted by the government).

- d. Rights and effective consultation for indigenous communities

- Strict application of Convention 169 and consultation mechanisms with veto power or binding conditions when projects affect water resources designated as collective goods.

- e. Encourage and fund less destructive alternatives

- Support and oversee trials of direct extraction (DLE) technologies under water and chemical standards, but only under controlled, audited pilots with clear environmental indicators; until clear improvements are demonstrated, prioritize the reduction of water footprints.