Original article: Educación pública en Chile: Cuando el mercado empuja al sistema a su límite

By Arnoldo Macker Aburto, Professor and Expert in Educational Management

Some appointments carry significant implications. Not due to a lack of capability from individuals, but because the trajectories and rationalities they embody send clear political signals.

In education, these signals hold more weight than initial speeches. The arrival of new leadership with a predominantly economic perspective does not signal a new direction; rather, it reaffirms the continuation of a logic that has characterized the Chilean educational system for over four decades: the understanding of education as a sector manageable under market criteria.

In Chile, public education has not been weakened by chance or natural inefficiency. It has been increasingly displaced by an institutional design that perceives education as a quasi-market, where schools compete for enrollments, funding, and social legitimacy; where the state funds demand rather than supply; and where the public sector ceases to be the structural core of the system and becomes just another actor, subject to rules it cannot control.

This model, established during the dictatorship, was not dismantled in democracy. Instead, it was managed, refined, and legitimized, differing in nuances but showing evident structural continuity.

The establishment of quality assurance systems, evaluative agencies, standards, rankings, and standardized tests did not correct the educational market; it merely made it more sophisticated. Under the guise of continuous improvement, a rationale emerged that measures, compares, and punishes, but rarely supports or understands the pedagogical and social complexities of public schools.

In this context, public education has seen a sustained decline in enrollments, not as a result of abstract free choice, but as a direct consequence of a design that encourages competition and penalizes complexity.

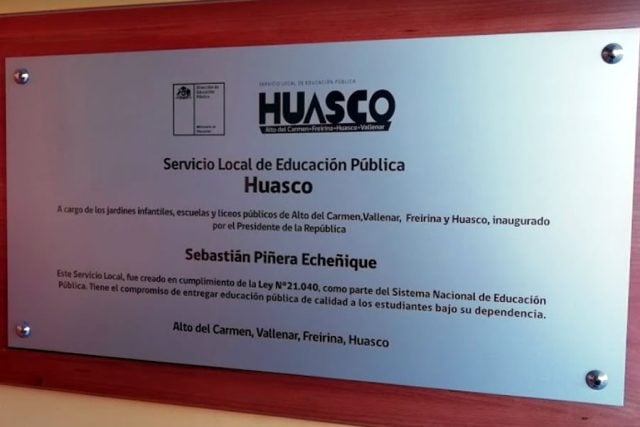

The decentralization of education and the creation of Local Public Education Services were touted as a historic opportunity to reclaim public education. However, their implementation has revealed profound structural limitations. Many Local Public Education Services inherited financial deficits, precarious labor conditions, and a highly regulated but inadequately pedagogical management style.

Instead of consolidating a strong educational state, what has emerged is an administrative state that controls, audits, and demands, but fails to sustain a long-term territorial educational project.

In this scenario, the Ministry of Education has operated more as a regulator than as an educational leader. It assesses, supervises, and adjusts, but provides little protection and even less support. Public education still lacks a clear, coherent, and sustained national project capable of addressing the segregation, inequality, and institutional fragmentation produced by the very model.

Adding to this structural logic is a persistent political practice: educational clientelism. Key decisions regarding positions, support, resources, and priorities are often assigned based on political convenience, conflict control, or communicational profitability rather than on pedagogical criteria or educational evidence.

Educational policy becomes defensive, aimed at managing discontent without altering the model that generates it. Partial results are celebrated, decontextualized figures are showcased, and success narratives are constructed that do not resonate with the everyday experiences of school communities.

The consequences of this approach are particularly severe in public schools. Enrollment-based funding punishes institutions that cater to students with the greatest social needs. Each drop in enrollment leads to fewer resources; fewer resources exacerbate deterioration; and deterioration accelerates student flight. Adjustments are normalized as technical inevitabilities when, in reality, they represent political decisions.

Teacher work is also profoundly affected. In a system designed like a market, teachers are no longer recognized as pedagogical authorities and are treated as service providers. The parent is addressed as a customer; the student, as a user. This displacement erodes the pedagogical bond, weakens school coexistence, and exposes teachers to growing forms of delegitimization and symbolic violence, often without effective institutional support.

All of this instills a particularly dangerous idea: that public education is residual. Necessary only for those who cannot integrate into the educational market. This notion is not only unjust; it is profoundly undemocratic. Societies with solid democracies uphold strong, prestigious public education systems protected by the state. In contrast, Chile has opted to weaken the common good and delegate the education of its future generations to a fragmented, competitive, and unequal system.

In this context, the new ministerial leadership does not signal a break but a consolidation. The political message is unequivocal: a rationale centered on economic efficiency, financial sustainability, and indicator management will deepen, even though this rationale has proven incapable of protecting and projecting public education as a social right.

Public schools cease to be viewed as the backbone of the system and are treated as adjustable variables. They are not strengthened: they are managed. They are not protected: they are regulated. They are not projected: they are maintained operationally as long as financial balances allow.

The consequence is neither uncertain nor future: it is already underway. Chilean public education is being pushed to its structural limits—financial, institutional, and symbolic. Each hidden closure, every normalized adjustment, every interrupted pedagogical project, and every weakened school community are not system anomalies but coherent expressions of a rationale that sees education as a cost, not a right; as a problem to be managed rather than a collective project to sustain.

Continuing down this path is not a technical inevitability nor an external imposition: it is a political decision. Deepening market logic from the ministerial leadership means accepting, either explicitly or implicitly, that public education is fragile, residual, and dispensable. It implies renouncing the construction of a common educational project capable of ensuring substantive equality, social cohesion, and democratic formation.

If the new leadership chooses to continue and deepen this course, Chilean public education will not only be strained: it will be pushed to its breaking point. And when a country pushes its public education system to the limit, what is threatened is not merely an educational system but the very possibility of sustaining a democracy that is not just formal but socially just and politically alive.

Arnoldo Macker Aburto