Original article: San Antonio, la ciudad negada: Crónica de un desalojo forzado por el abandono del Estado

By Constanza Lizana

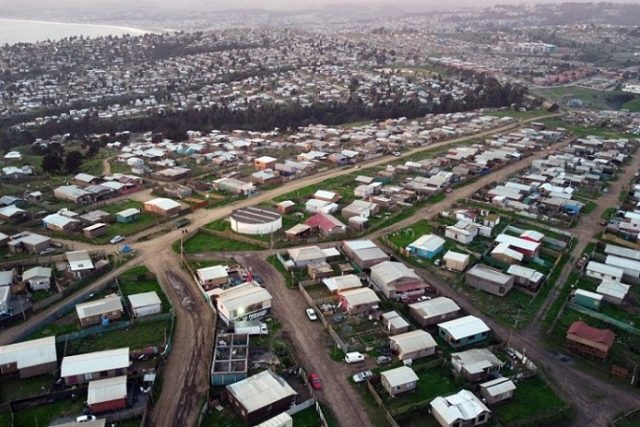

In 2019, amidst widespread social unrest, numerous families from San Antonio began clearing land to construct their homes in the Bellavista sector. This marked the inception of the largest land occupation in Chile, known as the San Antonio settlement.

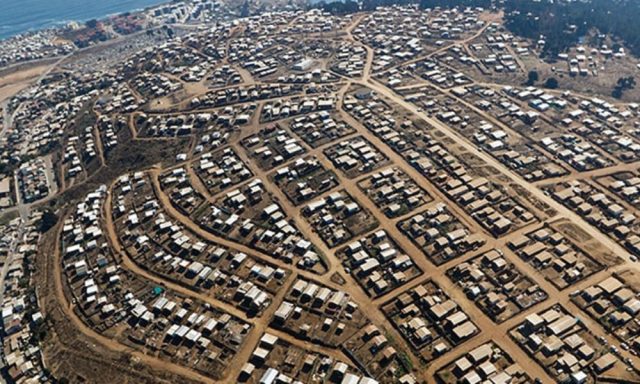

During the pandemic, this occupation expanded and became more established. Today, over ten thousand people reside in this area, which boasts wide streets, plazas, and community spaces.

This situation is not an isolated incident; the Valparaíso region contains the highest number of encampments in Chile, reflecting a country where access to housing is no longer a realistic possibility—not just for the so-called “most vulnerable,” but for broad sectors of the population.

Structural Housing Exclusion

According to a census by the Ministry of Housing and Urbanism, nearly 65.5% of households in the settlement are in a state of high social vulnerability, and 95% of residents lack a second home. These figures dismantle the narrative of individual exploitation: this is not speculation, but structural exclusion.

Most families belong to the active workforce, yet they find themselves outside the formal housing access system: lacking the ability to save, without access to mortgage credit, and often without real opportunities for subsidies. This is not a matter of effort; it’s a system that assumes everyone can incur debt, even when millions cannot.

Housing and Land: When Rights Become Privileges

Over the last decade, the cost of housing in Chile has risen significantly more than wages. The Housing Affordability Index (PIR) indicates that a typical family now requires 11.4 years of income to purchase a home; a decade ago, it was just 7.6 years.

The 2022 CASEN Survey confirms this pressure: 13.7% of households spend more than 30% of their income on housing costs, a clear indication of housing overload.

The problem is compounded by the sustained increase in urban land prices, which are increasingly concentrated and treated as financial assets. According to the CEP Bulletin No. 24 (January 2026), between 2010 and 2025, housing prices soared nearly 110%, while wages increased by only around 34%. The outcome is not surprising: cities are becoming more expensive, exclusive, and segregated.

When land and housing become investment assets rather than essential goods for living, access is transformed from a right into a privilege.

Available Land, But Withheld

The land where the settlement currently stands is owned by a real estate firm that has left it unused and without projects for over 30 years, despite its residential designation and location within the urban radius. For years, it was even taxed as agricultural land. This 14-hectare parcel, well-located and connected, could significantly alleviate the housing deficit in the municipality.

This is NOT an exception. In San Antonio—like many cities across the country—urban land is highly concentrated in the hands of a few, held for years without fulfilling its social function, awaiting higher future profitability. This speculation drives up urban costs and displaces families.

The State, whether by action or inaction, has allowed land to become stagnant capital, forgetting that urban land has a social duty.

Eviction: A Solution That Worsens the Problem

Proposing eviction as a solution is not only ineffective; it masks the failure of housing and land policy, shifting that burden onto thousands of families. Eviction does not reduce the deficit, restore rights, or resolve urban living conditions; it merely displaces precarity, tears communities apart, and multiplies social costs.

Even more alarming is the invocation of issues like crime or drug trafficking when the State has been absent during the installation, growth, and consolidation of the settlement. This absence—of control, planning, available land, and housing supply—is a direct contributor to many of the challenges that are now used to justify forceful interventions.

Responding with institutional violence to a structural need created by the very system deepens injustice and normalizes exclusion as public policy. One cannot neglect a territory for years and then only return with judicial orders and police force.

The State’s obligation is not to evict without alternatives but to relocate, plan, and reassign land—both expropriated and unexpropriated—using existing legal tools to provide real and secure housing solutions.

A Repeated History

Land occupations are not new. Following the 1982 crisis, numerous neighborhoods across the country emerged from similar occupations. From that experience came Law 18.138, which allows for the regularization of land designated for social housing.

Updating and applying this legal framework, along with reviewing subsequent restrictions such as Law 20.234 and its 2022 amendment, would facilitate the move toward institutional, rather than repressive, solutions; however, the parliament did not include the 2019 occupations in this amendment—a change that must be addressed.

A Warning for the Nation

San Antonio is not an exception; it is a warning. As long as we treat land as merchandise and housing as a reward, we will continue to create exclusion and conflict.

Land occupations are not the problem; they are the symptom. Either we build a fair and proactive land policy, or we will keep building inequality.

Constanza Lizana.-

The Citizen