Original article: El silencio contractual: Confidencialidad, subcontrato y desigualdad laboral

By Ronald Salcedo, President of the BHP Labor Federation in Chile, member of the Tarapacá Union

In the workplace, not everything that remains silent is protected for legitimate reasons.

Often, this silence doesn’t safeguard industrial secrets or strategic information; instead, it conceals labor realities that, if brought to light, would spark essential discussions about justice, equity, and dignity.

Within this tension arises the concept of confidentiality—a legal notion that is valid in its origin but merits closer examination in practice, especially from the perspective of those who rely on their labor.

Generally, confidentiality in the workplace refers to the obligation of employees not to disclose information that could negatively impact the legitimate interests of their employer, such as production processes, technical backgrounds, or business strategies.

Legal doctrine and jurisprudence recognize the validity of such clauses, as long as they pursue a legitimate aim and respect fundamental limits, including proportionality, necessity, and good faith. However, the reality of work demonstrates that, under certain circumstances, these clauses are applied in contexts that far exceed their original purpose.

Recently, we have heard from workers who have been offered to replace permanent employees in various tasks and productive areas, performing equivalent functions but under notably inferior contractual conditions.

According to their accounts, these offers originate from contracting companies that provide temporary services or that, in mining vernacular, exclusively supply labor without offering tools, equipment, or infrastructure—meaning the only productive element is the workforce itself.

In such schemes, labor intermediation becomes a business in its own right. Companies acting as intermediaries charge for merely providing workers, creating a chain where the primary value lies in the availability of individuals willing to work under more precarious conditions.

To safeguard these practices, many times, confidentiality agreements are mandated that significantly exceed the original intent of this principle, restricting the ability to discuss work conditions or modes of hiring.

Numerous testimonies agree that these situations are particularly challenging to report. A lack of documentary evidence, the fragmentation of workers, and especially the fear of losing the chance to earn a living for their families, all serve as factors that perpetuate these practices in silence.

What’s most complex is that these phenomena occur not only in informal or marginal economic spaces but can also develop within large companies, many of foreign origin, that operate within the legal margins and understand the limits of the regulatory system precisely.

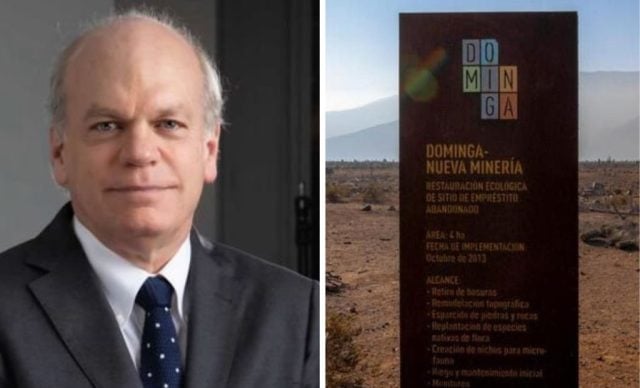

In the case of the Chilean mining sector, this process is not new. Over the last two decades, the expansion of subcontracting has profoundly transformed the work structure in this field.

What was initially presented as a mechanism for specialization and efficiency has, in numerous cases, resulted in production systems where workers performing similar tasks coexist under very different conditions.

The subcontracting law, which originally aimed to enhance the protection of outsourced workers, has not always succeeded in preventing the fragmentation of work from consolidating as a permanent tool for reducing labor costs.

This fragmentation also has significant social effects: it creates tensions among workers, feeds prejudices, and builds the false perception that the problem lies with those working under different conditions, when in fact the disparities arise from corporate decisions and regulatory frameworks that allow it.

In this way, the focus shifts from the structure that produces inequality to the workers themselves, deepening divisions that only benefit cost-cutting measures.

From an economic perspective, these practices are not neutral. The systematic reduction of labor costs through intermediation and contractual segmentation follows a logic well-known in political economy for over a century: the relentless pursuit of profit maximization by decreasing labor costs.

In simple terms, this means achieving the same productive outcome while paying less for the labor necessary to accomplish it. This logic, theoretically described as an increase in the rate of exploitation or accumulation of surplus value, results in wage disparities, precariousness, and fragmentation of the labor collective in practice.

Understanding these phenomena is not merely an academic or legal task; it is a fundamental necessity for the labor world. When workers can identify what confidentiality is, what its limits are, and when it ceases to serve a legitimate function to become a tool for obfuscation, a decisive step is taken.

Knowledge allows us to stop normalizing unjust situations and begin labeling them for what they are. The history of the labor movement shows that no significant labor rights have been spontaneously granted—each has been the result of processes of organization, awareness, and collective action. Understanding the reality of work is always the first step towards transforming it.

For this reason, strengthening analysis, organization, and denunciation against practices that undermine labor remains an essential task. No one will defend labor if those who sustain it day by day do not take action.

Identifying these practices, discussing them collectively, and reporting them through appropriate channels is not an act of confrontation, but an act of responsibility to the present and to future generations of workers.

Because when silence is used to conceal inequalities, breaking that silence is not just a right; it is also a means of defending the dignity of work.

Ronald Salcedo