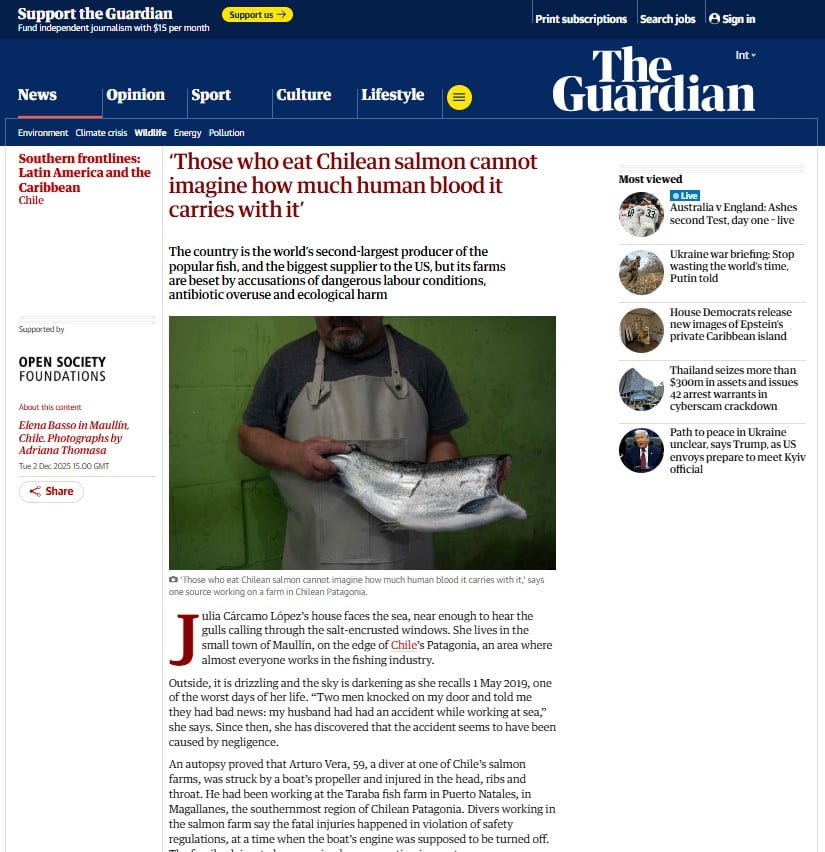

Original article: “Quienes comen salmón chileno no imaginan cuánta sangre humana lleva encima”: investigación de The Guardian apunta a muertes de buzos y daño a comunidades mapuche

The Human Cost of Chilean Salmon: A Guardian Investigation Reveals Worker Deaths and Community Harm

The Guardian’s investigation into Chilean salmon challenges the narrative of «export pride» by exposing a darker reality rarely seen by consumers in the Global North: worker fatalities, polluted rivers, and indigenous and fishing communities struggling to resist.

The British media notes that Chile is now the second-largest salmon producer in the world, after Norway, and the primary supplier of this fish to the United States. In just the first quarter of 2025, Chile exported over 56,000 tons to that market, valued at $760 million. Europe has also become a key destination: between 2003 and 2024, imports of Chilean salmon in the European Union surged from $56 million to $204 million, making the bloc the sixth-largest market for this product.

However, behind these figures, the investigation focuses on the conditions in which this salmon is produced, both at sea and in the rivers of southern Chile.

The Guardian’s Investigation into Chilean Salmon: The Death of a Diver in Patagonia

The report opens with the story of Julia Cárcamo López, a resident of Maullín (Los Lagos Region). From her home by the sea, she recalls May 1, 2019, when two men knocked on her door to inform her that her husband, diver Arturo Vera, had suffered an accident while working at a salmon farming facility.

Vera, age 59, worked as a diver at a farm in Puerto Natales, in the Magallanes Region. According to the investigation, an autopsy revealed he was struck by a boat’s propeller, sustaining injuries to his head, ribs, and throat, under circumstances where the engine should have been off, as safety regulations dictate. The family claims that a judicial compensation settlement was established following the accident.

The company operating the facility was fined for labor and safety violations identified by the Labor Inspection. The report indicates that the company was contacted for a comment but did not respond to requests for input.

The organization Ecoceanos, cited by The Guardian, states that in the past 12 years, the Chilean salmon industry has recorded the highest rate of accidents and fatalities in the aquaculture sector worldwide. Between March 2013 and July 2025, 83 workers have reportedly died in accidents linked to the industry, while Norway, over the same extended period of 34 years, reported only three deaths in the salmon industry.

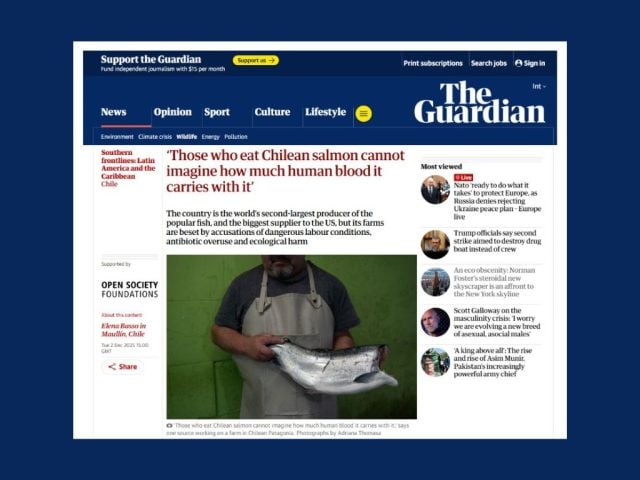

“Those who eat Chilean salmon have no idea how much human blood it carries,” claims one of the sources working at a farm in Patagonia, as reported by the British outlet.

Antibiotics, Pollution, and Impact on Artisanal Fishing

The report reminds readers that salmon are not a native species to Chile: the first fish were brought from Norway over 40 years ago during Augusto Pinochet’s dictatorship. Since then, the industry has exploded; from 1990 to 2017, production increased by nearly 3,000%, reaching over 750,000 tons exported to more than 80 countries.

This growth, however, has been accompanied by intensive practices that raise scientific and community concerns. The Guardian cites data showing that Chilean salmon farms used over 351 tons of antibiotics in 2024, a decrease from 563 tons in 2014, yet still a very high number considering studies indicate that between 70% and 80% of these antibiotics may end up in the environment. In contrast, Norway has reported practically zero use of antibiotics in its farming facilities.

The massive use of these medications not only affects marine ecosystems but can also promote antimicrobial resistance and the transfer of resistant bacteria to individuals consuming contaminated products.

Artisanal fishers interviewed in the report describe a decline in species such as sea urchins and mussels in areas near farming operations, making it increasingly difficult to sustain local economies tied to traditional fishing.

Mapuche Communities and Polluted Rivers in Southern Chile

The investigation does not stop at the sea. It also addresses the impacts of salmon farming in freshwater phases, particularly in the regions of La Araucanía and Los Ríos, where incubation, fertilization, and early rearing centers are located.

One of the cases highlighted in the report occurs in the Chesque Alto community in La Araucanía, which has been engaged in a long legal battle with the company Sociedad Comercial Agrícola y Forestal Nalcahue Ltda., dedicated to salmon production in the area.

Machi Angélica Urrutia, age 35, recounts that since the company’s establishment in 1998, the Chesque River began to change: fish and birds disappeared, and some sections of the river became reddish and viscous. In 2005, four cows died after drinking water near the company’s outlet; a veterinarian concluded they had ingested a high amount of formalin, a chemical used in salmon farming to combat parasites.

According to the article, the community managed to halt the company’s activities for about eight months in 2021, during which time fish and wildlife returned to the river, and ancestral ceremonies could be conducted in the water—activities that had been limited due to pollution. Currently, the company is facing an administrative sanctioning process but is still operational while this is pending.

Urrutia also reports practices of “incentives” to local residents, such as purchasing animals, to reduce opposition to the company’s presence. Simultaneously, she asserts that she can no longer gather medicinal herbs along the riverbanks or use certain sections of the river for Mapuche ceremonies due to the water’s condition.

Absent State and Lack of Effective Regulation

The report also voices Jorge Ampuero González, head of the Provincial Labor Inspection in Puerto Natales, who acknowledges that he lacks sufficient personnel and resources to effectively oversee an industry operating in isolated, hard-to-reach areas. His team of seven must supervise about 30 salmon farms but has no boats or helicopters to reach facilities that can require up to 12 hours of navigation.

Ampuero states that, in practice, each center can be visited one or two times a year, drastically reducing the real potential to change underlying labor conditions. He warns that the sustainability of salmon farming does not just depend on how many tons are produced, but on how it is produced and under what conditions for the workers and the territories where they are established.

The report mentions that Chilean authorities—such as the Ministry of Environment, the Undersecretariat of Fisheries, Sernapesca, and representatives from the industry grouped in SalmonChile—were contacted for their perspective, but it appears there was no success in these efforts.

As Chilean salmon continues to occupy shelves in the United States, Europe, and other markets, The Guardian’s investigation reopens a troubling question: what is the true human and ecological cost of the “pink fillet” that Chile exports to the world?