Original article: Las próximas guerras siempre estuvieron aquí: Cómo la ley posterior al 11 de septiembre y la Doctrina Monroe convergieron en el Caribe

By Michelle Ellner

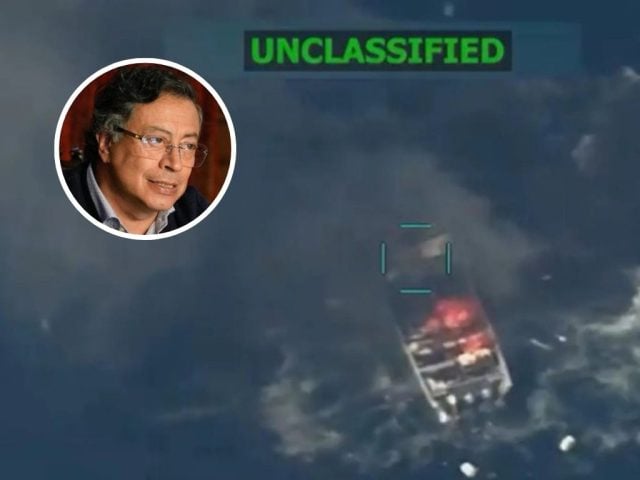

At the beginning of September 2025, the first U.S. missiles struck vessels in the Caribbean, framed by Washington as a «drug trafficking operation,» a sterile phrase meant to soften the violent imagery of incinerating human beings in an instant.

Then came the second attack, this time targeting survivors already struggling to stay afloat. However, as details emerged, the official story began to unravel.

Local fishermen contradicted U.S. claims. Families of the deceased stated that the men were not cartel operatives, but rather fishermen, divers, and small maritime messengers.

Relatives from Trinidad, Colombia, and Venezuela told regional reporters that their loved ones were unarmed and had no ties to the Tren de Aragua; they described them as fathers and sons working at sea to provide for their families.

Many labeled the U.S. narrative as «impossible» and «a lie,» insisting that the men were being demonized posthumously. UN experts have classified the killings as «extrajudicial.» Maritime workers pointed out what everyone in the region already knows: the route near Venezuelan waters is not a fentanyl corridor to the United States.

Nevertheless, the administration clung to its narrative, insisting those men were «narco-terrorists,» long after the facts had dismantled that version. In the post-9/11 U.S. manual, fear is a tool. Fear has become the architecture of modern war in America.

The U.S. did not emerge from the Iraq war into peace or reflection. It emerged into normalization. The legal theories invented and abused after 9/11—including elastic self-defense, limitless definitions of terrorism, «enemy combatants,» and global strike authority—did not vanish. They became the backbone of a permanent war machine.

These justifications have supported drone wars in Pakistan, bombings in Yemen and Somalia, the destruction of Libya, special operations in Syria, and another military return to Iraq. Behind every expansion of this global battlefield lies an American arms industry that profits from each intervention, pushing for policies that maintain the country in a constant state of conflict.

What we see today in the Caribbean is not an isolated action: it is the extension of a militarized imperial model that treats entire regions as expendable. The next wars have always been there because we have never confronted the political and economic system that turned endless wars into a profitable linchpin of American power.

A Post-9/11 Legal Framework Designed for Endless Wars

The Trump administration has put forth several overlapping legal arguments to justify the attacks, revealing a post-9/11 legal framework that stretches executive power far beyond its limits.

According to a detailed report from The Washington Post, a classified memo from the Office of Legal Counsel (OLC) at the Justice Department claims that the United States is engaged in a «non-international armed conflict» with alleged narcoterrorist organizations. Under this theory, the attacks are classified as part of an ongoing armed conflict, rather than a new «war» that would require congressional authorization. This approach is unprecedented: drug traffickers are criminal networks, not organized armed groups attacking the U.S.

A second pillar of the memo, as described by lawmakers to the Wall Street Journal, asserts that once the President designates a cartel as a Foreign Terrorist Organization (FTO), it becomes a legitimate military target. However, terrorist designations have never created war powers. They are financial and sanctioning tools, not authorizations for lethal force. As Senator Andy Kim stated, using an FTO label as «kinetic» justification is something «that has never been done before.»

The memo also invokes Article II of the Constitution, arguing that the President can order attacks under his authority as Commander in Chief. But this argument relies on another unfounded premise: that the vessels represented a significant enough threat to justify self-defense. Even lawyers within the government have questioned this. As an internal source told The Washington Post, «There is no real threat justifying self-defense—there are no organized armed groups seeking to kill Americans.»

At the same time, the administration publicly insists that these operations do not reach the level of «hostilities» that would trigger the War Powers Act because no U.S. military personnel were at risk. According to the administration’s own logic, that means individuals on the vessels were not participating in hostilities and thus were not combatants under any acceptable legal standard, making it impossible to reconcile the attack as «self-defense in a time of war» with U.S. or international law.

Under international law, executing individuals outside of a genuine armed conflict constitutes extrajudicial killing. None of these attacks meet the legal threshold of war. Since the individuals on the vessels were not lawful combatants, the operation risks violating both international law and U.S. criminal law, including laws on high seas homicide—a concern that reportedly contributed to the early resignation of Admiral Alvin Holsey, a resignation we now know was not genuine, but rather the result of his dismissal by Secretary of War, Hegseth.

The memo goes even further, invoking «collective self-defense» on behalf of regional partners. However, key partners Colombia, Brazil, and Mexico have publicly criticized the attacks, undermining the very premise of «collective defense.»

This internal contradiction is one reason lawmakers from both parties have characterized the reasoning as incoherent. As Senator Chris Van Hollen stated, «This is a memo where the decision has already been made and someone was ordered to invent a justification.»

And beneath all of this lies the most dangerous element: the memo’s logic knows no geographic limits. If the administration claims to be in an armed conflict with a «narcoterrorist» group, then under its own theory, lethal force could be used wherever its members are found. The same framework that justified attacks near Venezuela could, in principle, be invoked within a U.S. city if the government claimed that a «cell» of a cartel is present there.

If Trump truly believes he is leading «the most transparent administration in history,» then releasing the memo should be automatic. The American people have a right to know what legal theory is being used to justify killing people in their name.

For decades, OLC memos have functioned not only as legal advice but as the internal architecture that allows presidents to expand their war powers.

Bush’s torture memos treated torture as legal simply by redefining the term, calling it «enhanced interrogation,» thereby opening the door to years of covert operations and abuses. The memo on Libya claimed that bombing a country did not equate to «hostilities,» allowing intervention to continue without congressional approval. Other memos authorized targeted killings, including drone strikes against American citizens abroad, building the idea that lethal force can be used outside traditional battlefields without any trial, based solely on executive determinations.

In every case, the memo not only interpreted the law: it redefined the limits of presidential war power, almost always without public debate or legislative authorization.

The American people have a right to know what «legal theory» is being used to justify killing people in their name. Congress needs it to exercise oversight. Military members need it to understand the legality of the orders they receive. And the international community needs clarity about the standards that the U.S. claims to follow. There is no legitimate reason to conceal the legal basis for lethal action, except that the argument does not withstand scrutiny. A secret opinion cannot sustain an open military campaign in the Western hemisphere.

The Oldest Foundation: A 200-Year Control Doctrine

If the legal basis stems from the post-9/11 era, the geopolitical foundation is much older—almost ancestral. For 200 years, the Monroe Doctrine has served as a permission slip for U.S. domination in Latin America.

The Trump administration went even further by openly reviving it and expanding it through what officials called the «Trump Corollary.» This reinterpretation turned the entire Western Hemisphere into a «U.S. defense perimeter» and justified an increase in military operations under the guise of drug-fighting, immigration control, and regional stability. Within this framework, Latin America ceases to be a diplomatic neighbor and becomes a security zone where Washington can act unilaterally.

Venezuela, with its vast oil reserves, its sovereign political project, and its refusal to yield to U.S. pressure, has been a target for years. Sanctions have softened the ground. Misinformation has hardened public opinion. And now, attacks near its waters test how far Washington can go without provoking an internal rebellion. The term «narcoterrorism» is simply the newest mask of an old doctrine.

The attacks in the Caribbean are not isolated incidents. They are the predictable intersection of two forces: a post-9/11 legal regime that allows for the expansion of war without congressional approval, and a 200-year imperial doctrine that treats Latin America as a zone of control rather than a community of sovereign nations. Together, they form the logic that justifies today’s violence near Venezuela.

The Label That Opened the Door

After September 11, each administration learned the same lesson: if you label something «terrorism,» the public will allow you to do almost anything. Today, that logic is applied everywhere.

The cruel, decades-long blockade against Cuba is justified by claiming the island is a «state sponsor of terrorism.» Mass surveillance, border militarization, endless sanctions—all wrapped in the rhetoric of «counterterrorism.» And now, to authorize military action in the Caribbean, it is enough to attach the word «narco» to the term «terrorism.» The label does all the work.

The danger is not limited to foreign policy: following the assassination of Charlie Kirk, the same elastic definition of «terrorism» is being used domestically to justify attacks against NGOs accused by the administration of inciting «anti-American violence.»

The only reason Trump has not launched a large-scale attack on Venezuela is that he is still testing the waters: probing resistance within Venezuela, testing Congress, gauging media response, and testing us. He knows that nearly 70% of the American public opposes a war with Venezuela. He knows he cannot sell another Iraq. So, he probes, pushes, seeks the line that we will not allow him to cross.

That line is us.

If we do not challenge the lie now, if we do not demand the release of the memo, if we remain silent, «narcoterrorism» will become the new «weapons of mass destruction.»

If we allow this test case to go unanswered, the next attack will be a war. We are the only ones who can stop it. And history is watching to see if we learned anything from twenty years of fear, deceit, and violence.

Because the next wars have always been here, lurking. We just need the clarity to see them and the strength to stop them before they begin.

By Michelle Ellner.-