Original article: Un cerro a la izquierda en Bogotá

We are “Un cerro a la izquierda”. And here we are.

We formed in Valparaíso during the so-called social outbreak in 2019. At first, we were not a hill, but a group of musicians who gathered to record the album “República de Güiñas,” featuring songs by Sebastián Redolés, which we presented during the Popular Uprising across various hills of Valparaíso, supporting the movements at that time. Later, we reunited after a hiatus interrupted by the pandemic and the tumult of life.

The gathering and the flowing water under the bridge brought us a name: “Un cerro a la izquierda,” with Nacho Mena on drums, Carlos Espinosa on bass, Taku Tricot on electric guitar, and Sebastián Redolés on guitar, guacharaca, and vocals. Or, if you prefer: With Cerro Love, Cerro Respect, Cerro Tolerance, and Cerro Tonina.

When Edson Velandia invited us to the ninth Festival de la Tigra, set to take place in October 2025 in Piedecuesta, Colombia, we knew we were being called to something significant. Not in terms of what the market or music industry dictates, but in a different sense.

We were well aware of Velandia’s work, the singer who has been boldly raising his voice from Colombia, encouraging the noise and social mobilization of the Colombian people. We also knew about the existence of the community library La Bellecera and the Festival de la Tigra.

First Steps of an Unlikely Collaboration

While it is difficult to put into words what we experienced, if there is one person to start with, it’s Gina. Sebastián met Gina de la Hoz in Santiago around 2010 when he played with her in the band “la Chilombiana.” Gina, a Colombian musician and cultural manager, introduced Sebas to the love for Afro-Colombian percussion.

Moreover, as we know, during 2019, Chile and Colombia – like many other countries in Latin America and the world – sought to shake off the burdensome weight of the dominant elites, which entailed struggles that here and there are interrelated: a determination among the people that hadn’t been seen in decades, rampant state terrorism, and a strong frontline are part of a shared repertoire.

In this context, Velandia created songs for the Colombian mobilizations that we ended up hearing in Chile thanks to the uncertain digital algorithm. When Sebas heard them, he asked Gina if she knew him. She replied no, but yes to his songs, which are amazing, she said. Gina helped to get Edson’s number. And that’s how we established contact with Velandia, who gradually found his wings to visit Chile in 2021 and play with us in various places like El Canario or Cervezocracia in Valparaíso.

Four years later, we are invited by Velandia to the Festival de la Tigra in Piedecuesta, Colombia.

Un Cerro a la Izquierda in Bogotá

And here we are. We are Un cerro a la izquierda traversing Bogotá in an Uber on October 9, 2025, with a sun shining at 5:00 AM, as it is 9:00 AM in Valparaíso. Many motorcycles, many people heading to work everywhere, early on.

We came without Taku, our guitarist friend, who is not on this tour as he accompanies Mauricio Redolés, Sebastián’s father, playing in Europe. In his place, we brought Pata, a great guitarist and sound engineer from Quillota, who quickly became one of the crew, transforming into a great Cerro Empathy.

We soon arrived at our initial destination to experience a relatively unexpected event: being received by the very Ambassador at the official residence of the Chilean Embassy in Colombia.

This was arranged a couple of weeks earlier through some emails, where we introduced ourselves as Un cerro a la izquierda, seeking ways to survive in Colombia, receiving an excellent welcome from Ambassador María Inés Ruz, who warmly welcomes us at the Chilean residence in Colombia, showing us the enormous house that unfolded before our incredulous eyes and would host us for a few hours before we continued our journey. We talked with her about the current political, social, and cultural situation in Colombia while enjoying a splendid breakfast. Her kindness made us feel at home. After a while, she had to leave to attend to her duties, introducing us to her successor: Yanira Argueta, a Salvadoran fighter, feminist, former guerilla, who now works for women’s rights in El Salvador. With her, we discussed resistance, Salvadoran women, the complex political situation in El Salvador, Roque Dalton, and the popular music of her country.

That morning we rested there until noon, then said goodbye and went to meet Gina, who has been a complicit figure in this story, welcoming us with a generous smile at her home.

Once there, our first task was to find a bandeja paisa, the dish of Colombian gods. Unfortunately, we had no success. Instead, we had lettuce salads with fruit, peculiar fish to us, deadly arepas, and lots of tinto – surprising to us, as tinto refers to coffee there, because if you order “a coffee” you’ll get it with milk, while asking for a tinto gets you coffee without wine.

Then we headed to Latino Power, the venue where we played that night. Few would venture out at these hours in the streets of Chapinero – an area reminiscent of Recoleta mingled with Valparaíso’s Puerto neighborhood – and Latino reflected that: a modest crowd came to see Visajosx, Guache, and Un cerro a la izquierda, an absolutely unknown band in these alleys. The energy of the concert was fantastic. Playing with Gina infused the gathering with a chilombiana and berraquera vibe. Everyone who attended transformed into friends for decades, ¡Una chimba, marica!

Guache, a beautiful and magical ñero, provided absolutely stunning, monumental, psychedelic visuals. His warmth and human simplicity only grew as the days went by, as we would see him again in Piedecuesta, where we would repeat the experience. Being with him in the visuals felt like being caressed by leopards, mountains, skulls, and pure lightning.

That night we barely slept, awaiting the flight that departed at 5 AM on Friday heading to Bucaramanga, very close to our destination, Piedecuesta.

At the Foot of the Hill and a (Dis)appeared Poet

The journey was short, and by the time we arrived, we were already burning our energy reserves to stay awake, watching how a blazing sun rose among the mountains while trying to absorb the lush scenery of vegetation and cliffs along the route between Bucaramanga and Piedecuesta.

Again, many motorcycles flanked us, overtaking, challenging us, as if we were a clumsy and absurd obstacle mounted on 4 wheels. That familiarity and skill we see in people gliding on motorcycles has a different accent for us, who seem to have come from a distant island, with little sun.

Upon arriving in Piedecuesta, we headed to La Guarida, where we were offered a soup with potatoes, egg, arepas, and a tinto for breakfast – the last part still sounds like a joke to our ears. Nearby, a gentleman sat down whom Sebas thought was a worker taking a break for a cup of coffee. Little did we know that this man would become a master of this journey: when we greeted him, he introduced himself as el Caliche, drummer of Los Desadaptadoz, a punk band from Medellín formed in 1987.

After breakfast, some of us went to sleep, while others headed to La Bellecera to meet the library and its people.

La Bellecera is a self-managed library that arose from the recovery efforts of the neighborhood and managers in Piedecuesta. It was previously abandoned and is now dedicated to the cultural and community welfare of the Cabecera del Llano neighborhood, a popular area of Piedecuesta. In the center of the library -which serves as a venue for discussions, workshops, and various activities-, a Mapuche flag proudly decorates the room. This flag belongs to a people who claim ownership of themselves, where their tenacity, strength, and rebellion influence a vast territory.

In the walls of La Bellecera community knowledge flourishes and gathers. Those who frequent this space find a place for self-education, creation, and improvisation. It is also the operational base of the Festival de la Tigra, where its incredible production team and the dedicated volunteers work together.

When we arrived, Edson was there, glued to a phone, resolving festival issues, greeting us with waves in the air. We also met our compatriot Gabriela Flores, a beloved cultural manager and one of the architects of this trip alongside Taku and Sebas, who came out to greet us with Ekeko.

Finally, by noon, all the travelers were out cold, sleeping.

We woke up the same day we had gone to sleep. Our first day felt like two. It was truly a Foot of the Hill: we arrived very tired and had to close our eyes for a good while to try to reset ourselves. We spent the whole day this way. We knew that a busy Saturday lay ahead.

That Friday afternoon, we went to the Daniel Mantilla Auditorium for a singer-songwriter gathering, where we met several people we would see again in the coming days: Vishal, an Indian photographer carrying an analog camera from another century. Also, la Muchacha Isabel, a Colombian singer-songwriter with powerful songs, well-loved in Chile – whom we saw throughout the festival in various roles, from singing to washing dishes, participating in discussions, and applauding peers passing through the stage. Meanwhile, while we listened to Ezequiel Borra, Jesús appeared in the theater seats – a manager and worker of la Bellecera and the Festival de la Tigra. Talking with Jesús confirmed that we were definitely far away, where kindness from another time resides: “Whatever your need, count on me” – he told us in a profoundly moving Spanish, after organizing everything necessary for the workshop the next day.

When the concert ended, the rain began intermittently outside the Auditorium, and it was already getting dark in the warm city at the foot of the hill. There, we ran into Edson, who told us that at the Festival, he would introduce us to his father, German Velandia. Sebas knew that Velandia’s father was a comedian and asked Edson if he still worked as such. Velandia replied that he hadn’t for a long time: “Now his official occupation is to fight on Facebook.”

By then, it was completely dark; it was six or seven in the evening, and the rain was getting stronger. We walked to La Guarida to wait for the start of a Jam session that would not happen until much later when we would be sound asleep, two blocks from that place. In the meantime, we wandered quietly, trying to distract ourselves. Until suddenly, Caliche appeared.

The night wrapped us in a suffocating and rainy embrace at the doorstep of La Guarida, the same place where we had breakfast, which was slowly filling up with voices, drums, laughter, and seeds. True to our coastal tradition, we stayed outside sharing with the people, amidst the rain that caressed the mountains and Piedecuesta’s asphalt. Conversations with Caliche were powerful; he is a great connoisseur of Chilean and Latin American music and poetry. Through him, we delved into the transcendence and revolutionary weight of the place where we stood, its history, and the martyrs that exist here. One participant in the conversation unexpectedly pulled out a book from his backpack and read us the poem “Desaparecidos” by Chucho Peña. It felt like an apparition; as if Chucho Peña had sought us out to reveal himself through that poem, speaking to us from another place:

“There are already so many

of our men and women

who simply do not appear

that it is enough

to found a homeland

of the exiled in death.

This is an excerpt from that, the last poem Chucho Peña wrote – who, they say, always sensed his death – before being murdered. It was so powerful to encounter that text that we decided to read it the next day during our performance at the Festival de La Tigra before starting “Blanco, Azul y Rojo,” a song we felt was united with this poem that night.

And there we were, receiving this outpouring of information through Caliche, and also through Marco, one of Manuel Chacón‘s sons, who approached us to share visions and experiences of struggle, and a group of rappers who, upon learning we were Chileans, became even closer. They admired the rap produced in Chile and, like Caliche, were familiar with our music. Astonished by the tobacco Nacho was smoking or by the photos of Valparaíso he showed them, one of them said amidst the crowd and rain: “I don’t know the sea, brother.” He was the youngest rapper of them all, from nearby mountains, familiar with rivers and canyons, carrying political and social rhymes from Bucaramanga.

It was a very intense night, where everything happened in just a few minutes: soon we found ourselves walking with Caliche towards the hotel to sleep, amidst the sound of drums and the unyielding rain, which would start banging even louder through the night.

Un Cerro a la Izquierda at La Tigra

The next day, Saturday, October 11, Un cerro a la izquierda presents itself early at La Bellecera. There, we began preparations for the workshop “Instrumentation of Chilean Popular Music” that we proposed to take to La Tigra. Our companions Nacho, Pata, and Carlos excelled in presenting from their respective instruments. Nacho’s presentation was simply masterful: he prepared a dissertation he had been developing in his mind for years. It was the first time he did it publicly: He began with the rhythm of diablada and its transformation into a political rhythm thanks to Violeta Parra and “Arriba quemando el sol” – thus bringing a heart to our marches and street struggles; he continued with the drums, showcasing its variations; provided a historical journey showing videos of the evolution of this rhythmic pattern and closed with a tribute to Pájaro Araya, the one who originally imparted this knowledge to our companion Nacho.

Afterwards, we played a couple of songs. Outside, many people approached us to greet and discuss our workshop. We particularly remember two gentlemen, musicians from Bucaramanga, who were thrilled with everything that was happening and familiar with the Nueva Canción Chilena.

Then it was Sebastián’s turn, who, along with the musician and singer-songwriter Sandino Primera -son of the monumental Venezuelan troubadour Alí Primera-, participated in the conversation “Heirs of the Rebel Song,” led by Venezuelan poet Indira Carpio, and also featuring Gaby Flores, who presented an excerpt from the documentary she co-authored, titled “Redo,” about Mauricio Redolés, Chilean musician and poet.

The discussion was an absolutely exceptional moment, featuring two sons of powerful and irreverent singer-songwriters from opposite latitudes of the continent.

While we were at La Bellecera, we met remarkably beautiful people, who pour their body and soul into this space. Chino Jesús – Second Librarian of La Bellecera – who supported us throughout, or Erika Alarcón – Coordination Manager – offering a tinto with a full smile, were always generous and welcoming, making La Bellecera a warm and endearing place. All festival workshops and discussions took place here. We particularly remember the statement from one of them made by Mauricio Meza, an environmental leader who said:

“We must confront transnational corporations with all the tools we have: in the technical, legal, and social movement spheres.

Mauricio, like many present there, has received death threats for his environmental work. Julia Chuñil is precisely remembered here for that.

A couple of hours later, it was time for soundcheck at Parque de La Libertad, where the Festival de la Tigra was happening, before proceeding with our performance.

By this point, while processing everything we had experienced, we could already confirm one thing: this is not an ordinary festival. Rather, it is what a festival should be: a gathering where humanity, meaning, and content are not at the service of the cultural industry, mass appeal, or marketing, but the opposite. The discussions, the Palestinian flag that crosses the park in front of the stage time and again, the Caravan for Water, the invited bands, the tinto, the murals painted simultaneously, all intermingle, braided together as an insolent force with a common horizon of profound community significance, where the people decide and govern, in stark contrast to that which obscures our humanity with genocides, torturers, and various psychopaths.

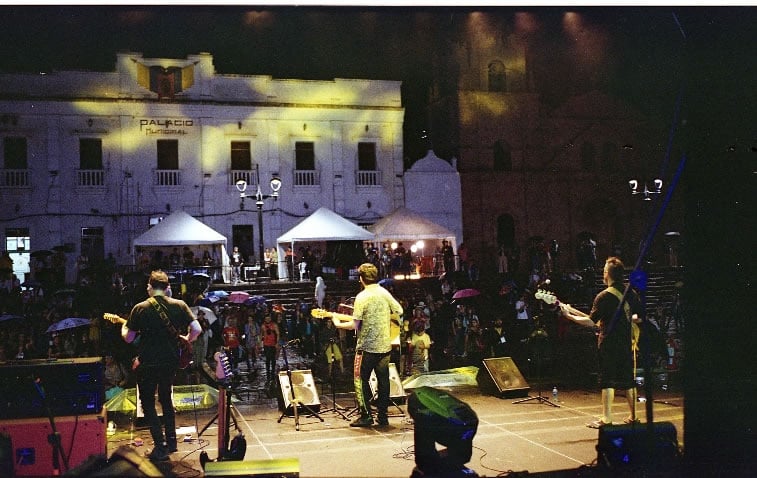

On the day of our performance at La Tigra, the clouds loomed, closing the sky over the Parque de la Libertad. Around noon, a light drizzle began to fall on the heads of attendees. As more and more musical groups performed, the drizzle thickened, emboldened by the music.

The stage was tremendous, featuring an equally incredible human team. Despite the rain, they looked up and responded: “Son, that’s what the plastic is for.” And just like that, onward.

Minutes before we began to play, Sebas dashed completely soaked to buy some pants. He got some that he would later find out belonged to the Club Atlético Bucaramanga, from a man who, while handing him the change, asked while pointing to the stage, “What competition is that?”

When we got on stage, everything happened in a sanctification.

The rain greeted us with a smile, recalling its recent past of fine drizzle. A few people listened directly under the intense downpour, while the vast majority did so taking refuge under awnings, umbrellas, ledges, and trees.

We played, and it felt like being in a jungle. After each song, shouts of joy emerged from many places.

When it ended, Edson came up to hug us. Gulping air and saliva while lamenting, he said: “The rain played a bad trick on us, man. It’s usually packed every time we do this festival.”

And yet, we responded with unabashed joy that for us, coming from Chile, where drought is rampant, coming to sing to them – even with this rain – is a gift we truly appreciate.

Many Hills, One Land

To this point, everything we have experienced has hit us hard. The compass has gone through an important recalibration.

The bands, the conversations, everything we have lived has acclimatized us to a new height. The La Bellecera Orchestra and the improvisation of a child playing the cowbell, the shamanic and masterful guaricha Adriana Lizcano, Edson and his indescribable spontaneity (“God bless creative drones and condemn killer drones!” he suddenly exclaimed into a mic at a drone filming Velandia and La Tigra in front of the stage), his family, the Guaricha Batucada, La Bellecera and its beautiful people, Caliche and Los Desadaptadoz, Manuel Chacón, his children, Chucho Peña, Sandy Morales, Vishal, the conversations and the exchanges with La Muchacha and Guache, Taku Chileno, the Champetos from Jujú, the Motilonas Rap, Sandino Primera and the Colibrí from El Chiquero, poet Indira Carpio, the Guapachosos of Carranga, everyone, was for us a true hemorrhage of stimuli.

During those days, we felt on the streets of Piedecuesta a Latin America that has resisted the attempts at annihilation perpetrated by the market, nationalist tales, and galloping fascism. Here, we found a strength that inspired us for what lies ahead.

Throughout the six days we spent in Bogotá and Piedecuesta, several individuals approached us to express how exemplary they found the determination of the people during Chile’s social outbreak. Despite all the criticisms or perplexity we might have felt, it was necessary to listen attentively and in silence. Because in these words, there was something greater, something not evident: The territory that welcomes us is immense. What happens in one place resonates differently a little further away, and a country is nothing more than a word we’ve believed from the enemy, as Roque Dalton teaches us.

“Only wells are built from above,” said Galeano. And another comrade here said, “the runoff is free.” Hence, it’s vital to listen beyond borders and what the media wants us to see and hear. Because from below we will give birth to our own, rooting – with the permission of our dead – in that underground homeland of which Chucho Peña speaks. Here, where those who inhabit remain, silently, that common ground. A land that, after all, is equally common to those of us standing here above. In one single land, in one single homeland.

An un Cerro a la izquierda.

Valparaíso, December 18, 2025.

Photos by Claudio “El Poc.”