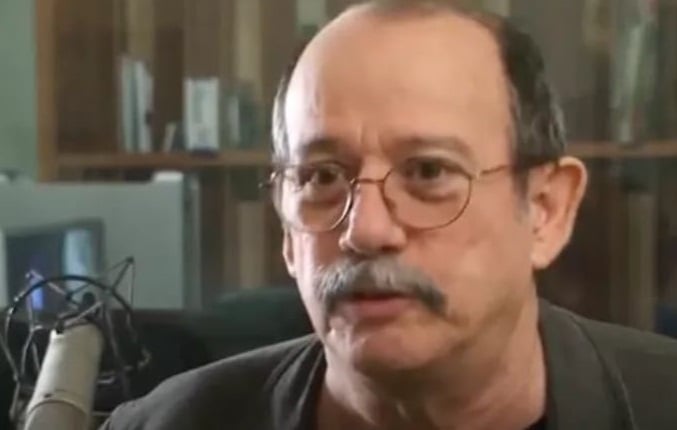

Original article: “Mientras más feo luce el panorama, más ganas tengo de crear belleza”: Entrevista a Silvio Rodríguez

Interview with Silvio Rodríguez: “The More Dismal the World Looks, the More I Want to Create Beauty”

By Berenice Ojeda Jara / Journalist and Cultural Manager

In this interview, Silvio Rodríguez refers to himself as a «troubadour of time». For many fans, he is a songwriter who, over more than six decades, has woven together emotion and awareness through a musical and poetic proposal connected to popular rhythms and the verse structures of Hispanic-American tradition, navigating the complexities of human contradictions and the intimacy of existence, as he notes in his responses.

This sensitivity and commitment have found a special place for him in Chile throughout his musical and personal journey. His first visit was in September 1972, when he arrived in the country alongside Noel Nicola and Pablo Milanés, invited by Isabel Parra. From that first encounter—where Victor Jara awaited him at Pudahuel—Rodríguez established a deep connection with the cultural and political memory of our nation.

Chile has served not only as a backdrop for applause and song but also as a source of memories and affection that have been renewed over the years. In 2025, after a seven-year absence, Rodríguez returned to Santiago as part of a Latin American tour, marking our country as a primary destination. He reconnected with both old and new audiences during a series of emotional concerts at the “Movistar Arena”, performing timeless classics as well as more recent compositions, alongside a band of renowned musicians.

This return was not just musical; it was also a heartfelt reunion with significant individuals. In Santiago, he spoke with figures like President Gabriel Boric, whom he called «friend», recalling shared experiences with Victor Jara during a visit to the Foundation that preserves the slain artist’s cultural legacy, now directed by his daughter, Amanda Jara.

Silvio Rodríguez’s career is a challenging map of intertwined periods; spanning from the dawn of the Cuban Nueva Trova in 1968—a movement that blended popular roots, social commitment, and lyrical exploration—to his current presence on stages across the continent, with albums that have become absolute references in the Latin American music repertoire.

TROVA

1. Since its origins, the trova has integrated the fusion of music and poetry, and this poetry has been tied to verse structures and forms inherent to a history, a language, and a cultural tradition that develops over time (hendecasyllabic verse, octosyllabic couplet, espinela tenth, Spanish romance). As a troubadour and ‘creator of songs’ from Cuba, what significance do you assign to these poetic forms, many of which appear in your work?

The Cuban trova is a fusion of music and poetry, not only because it has transformed literary forms common in poetry and verses of poets into music; it is, above all, because since the 19th century, when this expression began to take shape, Cuban troubadours identified deeply with the poetic. Indeed, the first troubadours were called poets by their admirers.

2. Which authors within this literary tradition resonate particularly in your work? Do the practitioners of the guajiro point, for instance, fit in here?

At 20, I titled a song “The Song of the Trova,” inspired by the impression left on me by Sindo Garay, one of the fathers of Cuban trova. By the time I emerged, the trova had already evolved, especially harmonically. Most of the great bolero and romantic song authors were troubadours themselves, like César Portillo de la Luz, Marta Valdés, José Antonio Méndez, Ñico Rojas, and others. I remember that the term singer-songwriter became trendy back then, likely influenced by the San Remo Festival and Italian artists who were composing and performing their own songs (Doménico Modugno, Sergio Endrigo, Gino Paoli). However, from the very start, I asked to be introduced as a troubadour; my identification went beyond profession to carry a certain class reasoning. At that time, troubadours were among the lowest paid in radio and television.

Although sometimes my work hints at countryside references, I believe my musical paths have been more urban in harmonic, rhythmic, and literary terms. The guajiro point, also known as Cuban, is an expression primarily rooted in rural life. Less than 100 meters from my birthplace, in San Antonio de los Baños, is the former home of Ángel Valiente, one of the most significant Cuban repentistas of all time. In Cuba, it is impossible to overlook the repentismo and the point, as these expressions have many followers; radio and television programs dedicated to that music have always existed.

3. Do these verse structures suggest to you ‘a music’ with particular or special characteristics?

Classical forms of versification stand out for their musicality. I have used them, though not excessively, because I do not compose in the written format. Rather, I tend to do the opposite: I structure a musical idea and then try to find the words to fit.

4. How do you understand the concept of “troubadour” today? Do you see yourself as a bearer of a tradition that both safeguards and innovates in this craft?

Like my entire generation, I consider myself a troubadour of the times and circumstances I’ve experienced.

RELATIONSHIP WITH CHILE

5. Announcing your concert in our country for September and October 2025, the response from your followers was almost immediate. Tickets for the first announced date sold out quickly, necessitating the addition of two new performances. This denotation reflects the profound admiration and affection our people have for your work. If I were to ask conversely, what does Chile mean to you on an emotional and creative level?

Chile was the first Latin American country that Pablo Milanés, Noel Nicola, and I visited, thanks to an invitation from Gladys Marín. It was September 1972, during the government of Salvador Allende, whom we were fortunate to see up close. We spent three or four weeks there, and it profoundly impacted my consciousness. I spent a lot of time at the Peña de los Parra, where we saw Inti Illimani, Illapu, Tito Fernández, Pato Manns, and Payo Grondona. One morning, we picked Victor Jara up and went with him to Valparaíso to sing at a university… Back then, the Alerce label was just beginning to take shape in Ricardo García’s mind, and popular muralism was exploding on the city’s walls.

Street battles occurred daily. It was an unforgettable trip, marked heavily by what happened just a year later.

6. In 2004, in Barcelona, you participated in the concert “Neruda in the Heart,” alongside prominent Cuban and Spanish artists. How do you value the work of Pablo Neruda? And what other Chilean authors are significant to you?

Neruda is very much Neruda: his poetic work is of universal proportions, even a Nobel Prize. I’ve always been attracted to Nicanor Parra, due to the declared roughness in his antipoems. In Havana, at Casa de las Américas, I once crossed paths with Enrique Lihn, and we also did a television program there with Gonzalo Rojas.

One of the Cuban troubadours I cherish, Teresita Fernández, was a great promoter of Gabriela Mistral.

7. Throughout your artistic journey, you have collaborated on several occasions with Chilean artists, most recently with Manuel García and Patricio Anabalón, among others. From this perspective, how do you view the current creative process in Chile?

I am not sufficiently informed on the current state to venture an opinion. I can only say that both Manuel and Pato are extraordinary singers, both have beautiful songs that are also very well rendered.

CAREER

8. If you could describe, in a few words, your artistic journey from the beginning to the present, which aspects, situations, and emotions would you highlight?

I believe I have been incredibly lucky. Born when and where I was; choosing a profession that feels like perpetual play, allowing me to remain a child forever. The cherry on top has been receiving applause and payment for doing what I felt like doing, which may seem excessive.

9. What creative interests does Silvio of 2026 have?

I have much to pursue, several musical projects slowly taking shape. I enjoy working this way, maintaining distance and returning to the same material later. New variations and ideas emerge.

10. What reflections and emotions lingered with you after the recent and successful tour through South America, particularly regarding the reunion with Chile and significant friends, such as Amanda Jara?

Beyond the Chilean audience, who at my age feels like family, I met relatives in Chile, and I saw many dear friends. The encounter with Amanda and her team from the Victor Jara Foundation was especially lovely. I let her know I had seen her as a small child when we picked her father up to go to Valparaíso. That day, she came out to the door, hugged him, and kissed him.

POLITICS

11. Years ago, you spoke about “revolutionizing the revolution.” Do you still hold this view? And how do you currently understand the term “Revolution”?

I have also said we should drop the R. Just think how that would sound.

12. Cuba continues to be a symbol of resistance against countless acts of sabotage against it, including Trump’s threats toward the island and other countries in the region, following his forceful political and economic control over Venezuela. What do you think are the factors that affect the preservation of its determination, considering the current internal crisis and external pressure?

In a sense, we have always been in crisis. It is extremely critical to contemplate a world where pity and altruism reign. This is the root of everything that happens to us.

13. From a human-political perspective: What mischievous dreams does “El Necio” of Silvio hold in the present?

Recently, at an annual troubadour event in Santa Clara called “Longina,” named after the song by Manuel Corona—one of the fathers of the first trova—someone asked me what advice I would give to young people. Ignoring that I dread that type of question—»they say only those who can no longer set bad examples give advice»—I’ll respond the same: The worse the outlook, the more I want to create beauty.