Original article: “Cuando los ricos cercan la ciudad…” Esteban Serey conversa sobre el derecho a la vivienda y a las urbes en Podcastpitalismo

This Tuesday marked the premiere of the first episode of the second season of Podcastpitalismo, a platform produced in collaboration between the Rosa Luxemburg Foundation and El Ciudadano.

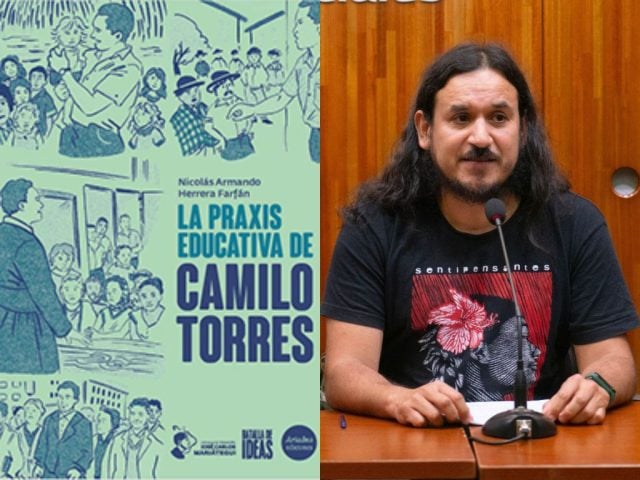

In this analytical program, lawyer and Director of El Ciudadano, Javier Pineda Olcay, interviewed Esteban Serey, also a lawyer from the University of Chile and a master’s holder in Urban Development from the Catholic University. Esteban Serey.

Streaming from the studios of El Ciudadano, inspired by the historic Cybersyn Project of Salvador Allende, the two discussed the right to the city and housing rights.

Below is an excerpt from the interview:

-In the editorial, we discussed this debate regarding the right to the city as a preliminary framework for the discussion on housing rights. Various theorists, including key Marxist reference David Harvey, discuss urban construction in the 20th and 21st centuries, addressing how capitalism has shaped urban development and coining concepts like accumulation by dispossession. Can you elaborate on the discussion regarding the construction of the city within a capitalist society and the reflections arising from the left and social movements?

-I think there are three main axes. One relates to capitalism itself and the concept of accumulation by dispossession, which translates into discussions about the right to the city based on displacements driven by capitalist accumulation cycles that favor some areas at the expense of others. Other theorists like Herbert Marcuse have focused on how these gentrification processes occur, involving material dispossession and symbolic dispossession, among other aspects.

Another distinct matter, I would say, involves these cycles of capital accumulation as a necessary consequence of the capitalist system, which constantly needs to reinvest surplus capital. Urbanization has played a notable role in the development of capitalism, particularly in Latin American countries.

Finally, as important as the previous points is neoliberal ideology, which distorts these cycles of capital accumulation, creating a chaotic geographical reality in various locales and at different scales. We cannot speak of a pure capitalist accumulation process; rather, we must reference the real-existing neoliberalism, as Brenner and Theodore referred to it in 2002, which illustrates the spurious way in which neoliberalism manifests across different places and scales. Additionally, this parasitic relationship with various forms of governance—authoritarianism, neoconservatism, and even social democracy—has shaped the landscape of our cities, leading to the understanding that today’s means of advocating for an alternative city paradigm stem from spaces of resistance.

-To conclude, Harvey distills what he calls revolutionary humanism. How do we understand this theoretical approach to capitalism in its various stages and its influence on urban development? For instance, the Santiago experience—how is Santiago constructed, and how do these theoretical elements dialogue with what we currently have in our city?

-The Santiago process is quite interesting. One could say—and this idea is not mine but Magna Vicuña’s, an academic from the Catholic University, who wrote about this back in 2015—that there is a juxtaposition between two types of states regarding urban planning and the growth of our cities.

On one side stands a managerial state that plans vertically by dictating norms to be followed by individuals and public and private entities responsible for implementing planning management. In contrast, a state that began showing signs of becoming a business-oriented state by the late 70s, where the logic of real existing neoliberalism prevails, has guided our planning history in Greater Santiago.

The intercommunal regulatory plan of Santiago, the PRIS of 1960, was a regulatory plan that categorically defined zoning, and the different uses of land, reserving spaces for municipalities to have obligatory construction areas, in accordance with what was established under the General Law of Urbanism and Construction from 1953—areas designated expressly for densification in terms of housing and residential needs.

However, this intercommunal regulatory plan defined an urban limit that, by the late 70s, with the National Urban Development Policy under Supreme Decree 420, amended this plan, expanding the urban limit of Greater Santiago by 60,000 hectares, approximately 160% of the existing urban area at that time. This marked a transition where the state ceased to guide the planning of our city, relinquishing that power to the market to decide the best use of resources and where those resources should be allocated.

Under this dynamic, the 1980 Decree Law 3.516 allowed for the subdivision of agricultural zones into parcels of 5,000 square meters as a minimum prior subdivision. This created pressure and led to two main effects: first, it enabled all these areas incorporated into the Metropolitan Region as part of the urban limit to be subdivided into small plots and sold, which resulted in significant urban sprawl dictated entirely by market decisions. Real estate promoters, through public-private agreements and under more or less transparent pressures on state administration, began to consume the city, consolidating this growth while generating little outcome, consequently increasing land speculation.

That is, owners of large plots brought into this metropolitan area, suitable for residential or other similar uses, do not develop these areas immediately, waiting instead for the city to grow through state and private investment, thus increasing their land value. This has resulted in areas like Tiltil or Lampa serving as illustrative examples of this process.

Moreover, as a closing thought, the implementation of Decree Law 3.516 creates an essential issue regarding the growth of urbanization and who finances it. Not only does the state cease to plan for the city’s growth, where it will go, and what public goods will be included, but it also passes the responsibility of financing urbanization onto the private sector—starting from this reform in the late 70s and early 80s.

Therefore, where does the city grow? Who invests in that urbanization? What public resources are available to support residential growth? These decisions are left entirely to the market. The state stops directing urban planning, and this cannot be reversed, even with the return to democracy in 1990.

In 1994, efforts were made to reconnect with the principles of the 60s, but it proved impossible due to real estate pressure and the preference for growth conditioned by certain urban incentives and development projects, which incentivized private actors to continue deciding, overshadowing the state’s planned directives regarding city growth, the scale of that growth, and the costs of speculation on land. Social housing was tied to that.

-I want to ask you because you’ve detailed the evolution of city construction, especially Santiago, and in general, all cities in the country, where they have been left in the hands of the market, where property owners, mainly real estate developers, decide where to invest and construct. In terms of historical recovery experiences, where would you say Chile had a strong urban planning experience, or which other countries, with certain nuances, illustrate interesting approaches to thinking about housing rights beyond market logics?

-It is challenging to discuss fortunate urban experiences due to the inherent nature of capitalism and the neoliberal phase that sustains the uneven development of cities, privileging certain cycles of capital accumulation in some geographic landscapes at the expense of others.

Nevertheless, there are some interesting experiences concerning land management, which I believe is a crucial pillar we must address today to potentially reverse how the market consumes urban growth and its prospects. This relates to land management strategies.

For instance, community land trusts, one notable example being Martin Peña in Puerto Rico, provide a model of shared land ownership among various individuals who cooperatively utilize land without necessarily becoming owners, while still benefiting from everything above the soil. Implementing these models would necessitate some legislative reforms to separate rights of ownership and building rights, but I see this as a significant direction for cooperativism in Chile regarding housing issues.

There are also engaging experiences in the Netherlands with community-owned housing in Amsterdam, as well as initiatives in Spain, particularly the interactions fostered between young individuals and elderly populations. These shared living spaces promote interaction, maintaining community administration roles for both groups, thus allowing each demographic to contribute to upkeep and internal governance decisions.

Senior citizens reconnect with roles that empower their societal contributions, countering the narrative that views aging individuals as burdensome. I think these successful examples should be considered in discussions about housing, specifically.

Regarding urban development, the most fortunate instances have consistently involved significant state presence in zoning and defining urban limits. In this sense, early 70s Greater Santiago aimed at becoming a notable example of achieving a more equitable, just, and integrated city, but the military coup extinguished that possibility.

-The coup even halted the expectations for metro development, which had been envisioned in the 1970s and is integral to the right to the city—not merely housing construction. Transitioning back to housing, let’s discuss how the perspective on the right to housing intertwines with the right to a dignified home. What is the landscape we encounter in a neoliberalized Chile where capitalism has ravaged urban fabric?

-The concept of dignified housing encompasses various interpretations; however, key attributes of the right to housing—including adequate living conditions—stand out. I believe that since 2010, the Chilean system has made notable advances, particularly driven by grassroots movements advocating for higher standards in housing quality amid the failures of 1990s housing policy that focused on mass construction without regulation on quality.

Today, the quality of social housing far exceeds what the system could provide in the earlier part of the 1990s.

It is worth highlighting comparisons—for example, the housing complexes like Bajos de Mena, which have garnered notoriety, were constructed with confined masonry, sized at about 40 square meters, suffering from poor ventilation, lack of lighting, and overcrowding. In contrast, current developments now range between 60-62 square meters, featuring minimum standards for indoor spaces and necessary amenities, allowing for at least three bedrooms and a full bathroom with laundry areas.

Additionally, the quality of single-family homes has improved similarly in terms of size, materials used, and living conditions regarding ventilation, among other aspects, leading to distinctly different realities. Bajos de Mena stands at the cusp of an urban regeneration process, where previously low-quality housing solutions are driving the demolition of buildings for complete neighborhood reconstruction. Today’s housing policies deliver better solutions equipped with thermal fixtures, thermopane windows.

I believe that, in this regard, social housing, aside from interior finishing differences with private market housing, holds comparable standards and should not be perceived with envy when set against private sector developments.

Below, you can watch the first episode of the second season of Podcastpitalismo: