Original article: «Estoy alejado de todo, pero no estoy alejado de nada»: El último diálogo con el arquitecto Sergio Larrain, fundador del Museo Chileno de Arte Precolombino

Interview by Mariana Hales

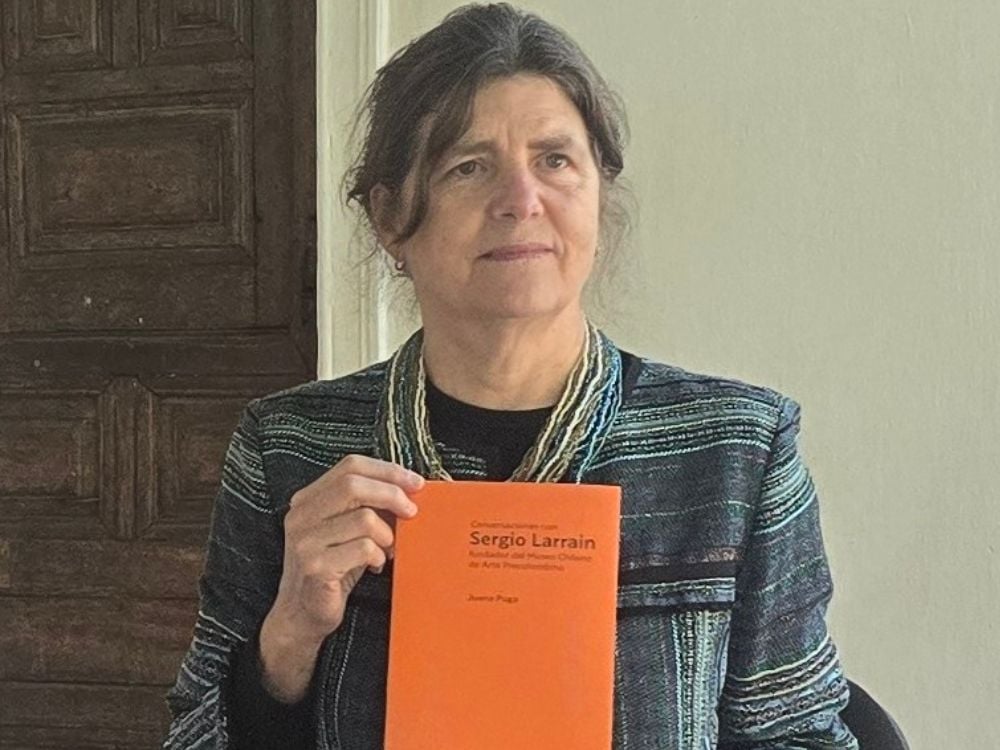

In Conversations with Sergio Larrain, Juana Puga invites us to hear the intimate and insightful voice of her grandfather, the architect and founder of the Chilean Pre-Columbian Art Museum.

The book, a culmination of conversations from 1988, not only reconstructs his professional journey but also delves into his philosophy on art, beauty, spirituality, and the meaning of life.

Puga effectively captures the essence of a man who lived in constant search, driven by insatiable curiosity and profound faith in the transformative power of art.

Beyond being a biographical account, the work reveals an intergenerational connection: the visionary architect dreaming of a museum for the Americas and his granddaughter, who reconstructs the family and cultural memory of the country through writing. Each page conveys the warmth of their generational dialogue, awe at Larrain’s coherent life choices, and the effort to preserve his voice in a fading collective memory.

In the presentation, you mention that your grandfather allowed himself to be “seduced by the exercise of narrating his life.” What did you feel as a witness to this process where personal storytelling becomes almost a final soliloquy?

It was the first time I realized how meaningful it can be for an older person to reflect on and interpret their life. I felt privileged to be the custodian of the treasure of his memories and narrative. A bond formed between us that brought us close together. Naturally, it made me consider my mother’s life and my own alongside my siblings. I owe this gift to my sister Cecilia, who suggested that I undertake this biography.

You chose to start the book with the last segment of the conversations, when he spoke of his present and his involvement with “Christians for the New City.” Why did you decide to alter the chronological order and start from that spiritual point?

In the brief biography I wrote for a book on Sergio Larrain as an architect, published in 1989, I adhered to the chronological order. However, I consciously placed the final fragment at the forefront, where Larrain discusses how the spiritual movement Christians for the New City has profoundly impacted his life and that of his wife, Pin.

He states: “Our life is taking on full meaning. Our detachment from worldly things is much deeper today, and I believe we look at death with great peace, a peace that I hope God preserves for us (…) I am removed from everything, but I am not removed from anything” (p. 41).

This was the grandfather I conversed with. The entirety of his life journey stems from this present moment. The narrator is an 83-year-old man who has lived intensely, given much of himself, and now retreats to pray, rest, and reflect on his life. Hence, the intention was for readers, just like me during our conversations, to know who they were «listening» to and understand his disposition before diving into his story.

However, the book at hand, Conversations with Sergio Larrain, Founder of the Chilean Pre-Columbian Art Museum, begins precisely with Larrain’s reflections on the Museum and its foundation. This new interruption in chronological order serves to highlight the pivotal moment the book focuses on.

In the chapter about the creation of the Chilean Pre-Columbian Art Museum, Sergio Larrain states that creating the museum was “inscribed from the beginning in his vocation.” How do you interpret this idea of destiny or vital coherence in his story?

In an interview with Humberto Heliash in 2008, Larrain mentioned that at 16 or 17, he was already buying art books and Gothic or Romanesque art objects. His passion for collecting began at a very young age. In Europe, his aesthetic judgments matured, giving rise to his enthusiasm for “the earliest expressions of humanity in art.” Consequently, when he returned to his roots, his country, and our continent, his passion for the pre-Hispanic art, of which he knew nothing as a child, was awakened.

Taking this notion of destiny that runs through his narrative, I decided to title my introduction to his book Sergio Larrain: A Journey Towards Earth and Essence.

The text recalls his childhood and the discovery of primitive art in Paris, a turn that would shape his outlook. Do you believe this shift in sensitivity also served as a means of emancipating himself from his family background and social class?

Sergio Larrain states, “Life changes you a lot if you don’t harden too much” (p. 22). It’s clear that the life he experienced molded him. His “thirst for knowledge,” curiosity, and significant artistic sensitivity were nurtured by his intense early strolls through Paris with his brother Pepe as a mentor, through extensive reading, and the classes taught by the sought-after professors.

All of this helped him distance himself from the bourgeois art in his childhood home or the French art of the Louis eras while developing a taste for primitive art. However, I do not believe he felt the need to emancipate himself from his family environment or social class. He did not need to break free to achieve his dreams. I never perceived that rift in him.

In the chapter about Le Corbusier, Larrain describes his conflict between the emotion of primitive art and modern rationality. How did you interpret the dialogue between these two forces within him?

There exists a tension between looking forward (what modern art and architecture propose) and recovering the past (what it means to reevaluate primitive art).

Sergio Larrain promotes modern architecture while bringing the new air of the old continent to Chile. He rejects what he calls “facade architecture,” overly ornate (such as that of the Museum of Fine Arts). Cities have expanded and densified. It is essential to adopt new housing solutions and optimize space use.

However, for Sergio Larrain, this does not mean turning away from the past. The foundation of the Chilean Pre-Columbian Art Museum stands as the most evident proof of his unwavering love for the pre-Columbian culture.

Although he advocated for modern architecture due to its rupture and innovation, his free spirit did not prevent him from looking back and choosing an adobe home. “Today I live in a house of clay and tile, and I feel comfortable and at home with clay and tile,” he confesses.

In the account of his time as a councilor and his encounter with Pablo Neruda, a politically engaged man driven by his faith emerges. What did this reveal about his perspective on the public responsibility of art and architecture?

My grandfather made it clear to me that he never belonged to any party. He was not a politician. He was primarily concerned with what was happening in the realm of art. His interest in Pablo Neruda’s proposal to help defend against Nazism in Chile and Latin America arose from his awareness of the danger it represented. Moreover, he loved grand challenges, and this was undoubtedly one of them. He never sought to be a councilor for the Municipality of Santiago or Chile’s Ambassador to Peru. Opportunities arose, and he took them very seriously. Faith, however, guided his steps, especially after the death of his youngest son in 1951.

When he speaks of the “Christians for the New City” movement, one can sense a tranquility and detachment from material concerns. Do you feel that this moment closes his biography with a kind of inner reconciliation?

Rather than a “reconciliation,” since it was not about reconciling things or reconciling with anything, I would say he underwent a process of “inner renewal,” having relinquished control over many aspects and found peace.

In your final postscript, you again quote his words about “the most primitive art” as something that touched his heart. What connection do you see between this aesthetic quest and his spiritual dimension, both in his work and personal life?

As I mentioned, the presentation I am preparing for this book is titled Sergio Larrain: A Journey Towards Earth and Essence. I believe this journey involved shedding everything he considered trivial and achieving the inner renewal we discussed. This is evident in his choice to eschew living in a modern house he built himself, with large spaces, a swimming pool, and a vast garden, opting instead for an old Chilean adobe house. At one point, I said living there felt like being in a convent. The silence and light in that house, filled with classical music and beautiful floral arrangements made by Pin, brought him peace.

Interview by Mariana Hales.-

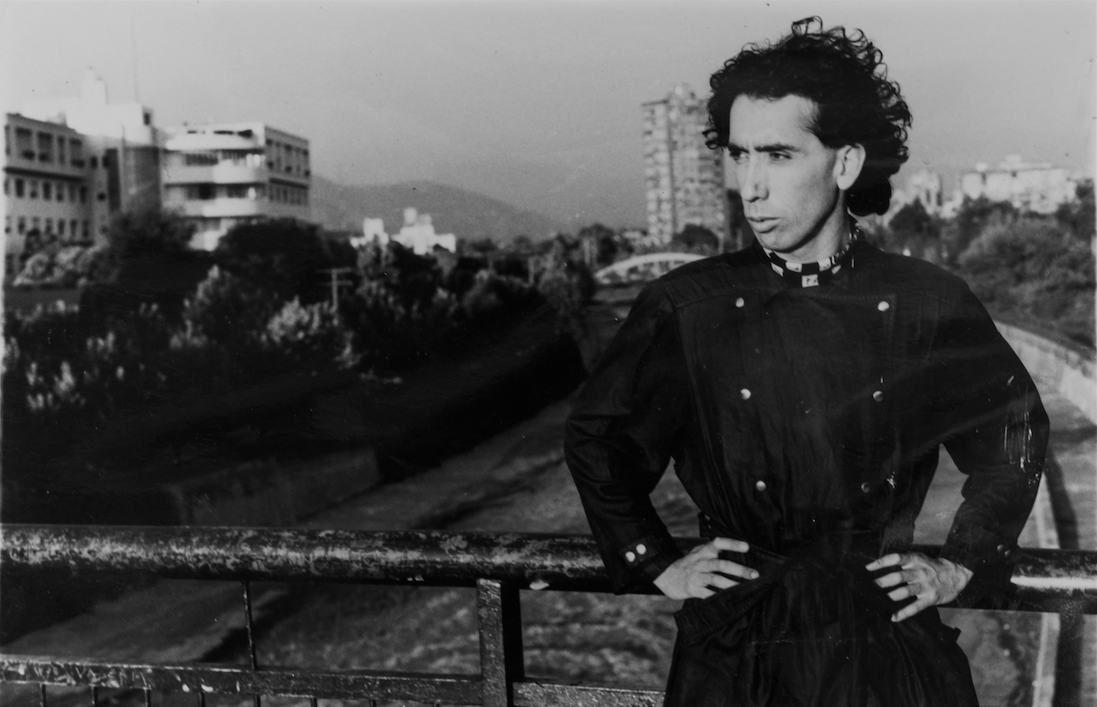

Cover Photo of Sergio Larrain: UC University Magazine