Original article: Ley Lafkenche: Aclamada en el mundo este 2025, mientras en Chile lucha por sobrevivir al asedio político y empresarial

2025: Lafkenche Law, a Global Model for Indigenous Rights and Marine Conservation, Survives Legislative and Judicial Siege in Chile

GLOBAL CONTRIBUTIONS AND RECOGNITION OF THE LAFKENCHE LAW

In 2025, Law 20.249 or the Lafkenche Law has solidified its status as a global benchmark. The annual UN report on oceans and human rights, prepared by Special Rapporteur Astrid Puentes Riaño, acknowledged it as an «exemplary model» and a «global standard» for protecting indigenous rights and fostering inclusive ocean governance.

Puentes emphasized that this law, achieved after decades of Mapuche-Lafkenche struggle, empowers communities to manage coastal marine areas for activities like fishing and ceremonies, safeguarding their cultural, spiritual, and economic ties to the sea.

Its implementation exemplifies inclusive and sustainable governance. In Hualaihué, the Coastal Marine Space of Indigenous Peoples (ECMPO) Mañihueico-Huinay, the largest in the area at 83,000 hectares, incorporates 19 indigenous communities, 32 fishing unions, 55 sea farmers, and dozens of local stakeholders into its management plan.

This model is also reflected in places like Apiao and Caulín, where the reality shows that ancestral uses, artisanal fishing, and other economic activities can coexist, harmonizing conservation with local development.

The year concluded with a significant administrative milestone: the Undersecretary of Fisheries and Aquaculture (SUBPESCA) approved the bi-regional ECMPO «Tirúa-Danquil,» requested by twenty Mapuche-Lafkenche communities from the Biobío and La Araucanía regions. This progress signifies a historic recognition of ancestral territorial management.

POLITICAL, JUDICIAL, AND MEDIA SIEGE TO WEAKEN IT

Ironically, while being celebrated internationally, the Lafkenche Law faced a systematic offensive in Chile aimed at its modification or repeal. The year started with a crucial ruling from the Constitutional Court (TC). On January 9, 2025, the TC declared unconstitutional Article 48 of the 2025 Budget Law, a provision pushed by National Renewal legislators, led by Mauro González, that sought to suspend the processing of new ECMPOs for one year. The Court ruled that the regulation «violates indigenous rights» and that «financial pathways in the Budget Law cannot be used to alter existing laws».

Despite this setback, the lobby to amend the law progressed in Congress. On April 29, the Senate’s Maritime Interests Commission advanced a particular reform project for Law 20.249, driven by senators such as Fidel Espinoza and Carlos Kuschel, among others. This motion, processed without indigenous consultation—an essential requirement of ILO Convention 169—aims, among other points, to limit requests and include «negative silence.» Lorena Arce from the Citizen Observatory warned that «none of the proposed modifications are necessary,» pointing out that the issues are administrative, not legislative.

The salmon farming industry has been identified as the primary proponent of this change. Loreto Seguel from the Salmon Council and Tomás Monge from SalmonChile publicly stated that the law generates «uncertainty» and «conflict.» However, official data contradict these claims of abuse: an information request to Sernapesca revealed that, in 17 years of existence, there has not been a single formal complaint of misuse or violation in the ECMPOs. «Legislating based on rumors without evidence is an act of irresponsibility and institutional racism,» was denounced by the Coastal Spaces Platform.

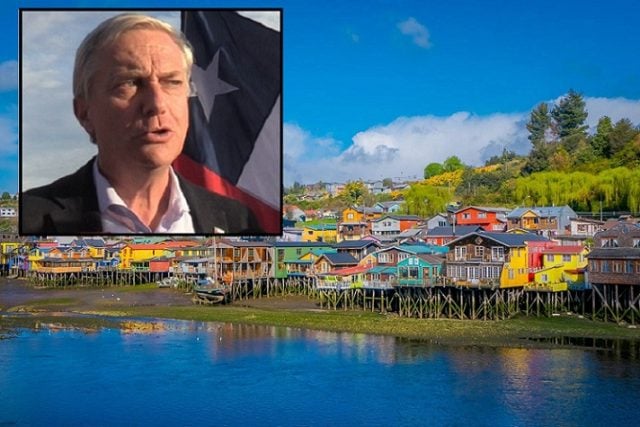

The offensive also featured an aggressive political-media component. While on the presidential campaign trail, José Antonio Kast claimed that the law «facilitates abuses» and proposed vetoing pending requests. Johannes Kaiser from the PNL went further by suggesting its elimination, labeling it «anti-Chilean indigenousism.»

In the media, newspapers such as El Mercurio published headlines like “Requests rejected… that endangered 368 aquaculture concessions,” information which geographer Álvaro Montaña described as «a distortion, a false news report,» reminding readers that the law prohibits granting ECMPOs over existing concessions.

At the local level, communities experienced delays and arbitrary rejections. In Aysén, the CRUBC prompted a Supreme Court ruling and rejected for the second time the ECMPOs of the Antünen Rain and Pu Wapi communities, ignoring their proposals to reduce the requested areas by 50% to accommodate salmon concessions.

In Los Lagos, Regional Governor Alejandro Santana was reported to the courts for “illegal and arbitrary delay” in voting on the Linao and Chadmo ECMPOs, keeping processes stalled for over 13 months.

Violence also played a role: Williche leader Miguel Raín from Caucahué (Chiloé) received death threats in July 2025, linked to his defense of an ECMPO, prompting MP Jaime Sáez to request urgent protection from the INDH.

Finally, indigenous peoples like the Chango have firmly expressed their rejection of any modifications, stating that a process without consultation «constitutes a severe violation of our collective rights.»

Despite the siege, indigenous resistance and the TC ruling of January 2025 emerged as critical bastions defending this law, which concludes the year as a symbol of global struggle and a model under fire in its own country.