Original article: Caso Quilleco: juicio vuelve a suspenderse por falta de jueces y agrava denuncias de irregularidades

The trial for the Quilleco Case has been postponed for the second consecutive time due to a shortage of judges at the Oral Court in Los Ángeles, less than 24 hours before it was scheduled to begin, keeping five Mapuche defendants in preventive detention for over two years without a final ruling. The defense has labeled this as an «outrage» that infringes on due process and the right to a timely trial.

In an interview with El Ciudadano, attorney Rodrigo Pizarro highlighted that five political prisoners from the Mapuche community have spent more than two years in preventive detention awaiting a trial that has yet to materialize. He explained that judicial authorities have delayed the most critical phase of the case on two occasions, violating basic international human rights standards such as due process and the right to a timely trial, obligations which the Chilean state is expected to uphold, yet according to Pizarro, seem only to apply to certain individuals.

“Since October 13, 2023, five defendants in the so-called Quilleco case, charged with their alleged involvement in two incidents of arson against forestry machinery and a supposed attempted homicide of police officers, have been under the most severe precautionary measure of our legal system while an investigation led by the controversial Prosecutor Juan Yañez Martinich is ongoing. Additionally, in April 2024, Rafael Pichún Collonao was added to the list of those imprisoned,” Pizarro stated.

Pizarro asserted that despite multiple irregularities during the investigation—such as a formal reformulation that he claims exceeded the limits set by Chilean laws—the case has proceeded with the expectation of finally reaching an oral trial. He maintained that this would be the first opportunity to genuinely discuss the innocence or guilt of the defendants, who have no prior criminal records and should fully enjoy the principle of presumption of innocence, which has “simply not occurred” in this case.

The Oral Criminal Court in Los Ángeles had initially scheduled the start of the oral trial for October 10 of this year. However, just days before the date, the court communicated, without any request from either party, the decision to reschedule it for February of the following year.

This means that a court of the Republic, which should be impartial and act upon requests from the parties while upholding fundamental rights, chooses to postpone the judgment of detained persons by at least four months, solely based on a «bottleneck of trials» and the court’s overloaded schedule,” Pizarro pointed out.

Pizarro explained that considering the postponement of the trial illegal due to infringement of the timelines set by law, all defenses petitioned the Concepción Court of Appeals for a writ of protection. The court ruled in their favor and explicitly instructed the Los Ángeles Court to expedite the oral trial.

However, he recounted that despite this higher court directive and the trial being scheduled for November 28, less than 24 hours before it was to start, the TOP postponed it once more. The court indicated—without any party requesting it—that there were no judges available to form the panel, leaving the defendants and their families, who had mobilized to support them, without a trial again.

“It is shameful that in a democratic state of law, supposedly respectful of due process, individuals who should be presumed innocent must bear the burden of prolonged incarceration solely due to the inactivity of the judicial power, which has, over the course of two months, been unable to appoint judges to fulfill their duties and to respect the duty of inexcusability in the adjudication of citizens,” the attorney stated.

Finally, Pizarro remarked: “One must ask, why are judges refusing to take on this trial? Why does the Court of Appeals not have sufficient authority to timely appoint those who fulfill their constitutional duty? If the Court of Appeals has no authority over its own judges, then who does?”

A Complex Case Marked by Serious Allegations and Over Two Years of Preventive Detention

The so-called Quilleco Case originated on October 13, 2023, in the commune of Quilleco, Biobío region, when—according to the prosecution—a group of hooded individuals allegedly intimidated a forestry worker, stole a truck, and burned two others in various locations around the area. The charges also include arson, robbery with intimidation, carrying weapons, and even a suspected attempted murder against police personnel.

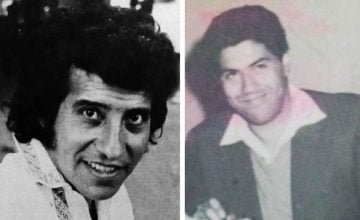

This is a complex and highly controversial judicial process, in which five Mapuche community members—Óscar Cañupan, Bastián Llaitul, José Lienqueo, Roberto Garling, and Axel Campos—are held responsible for these crimes. All have been in preventive detention for more than two years, a situation that their defenses and community members deem unjustified and politically motivated. Additionally, in April 2024, Rafael Pichún Collonao was also imprisoned.

The claims in the case have been propelled by Forestal Arauco (Angelini Group), a contractor of Forestal Mininco/CMPC (Matte Group), the Presidential Delegation of Biobío, and the Public Ministry. For the Mapuche communities, these companies—accused of land usurpation, environmental damage, and water precariousness—play a central role in the political criminalization of the autonomy movement.

Over two years, the defense has reported numerous violations of rights, such as late or incomplete delivery of the investigatory file, restrictions on the presence of defendants at hearings, the use of protected witnesses, limitations on the accompaniment of traditional authorities, and repeated cancellations of key hearings.

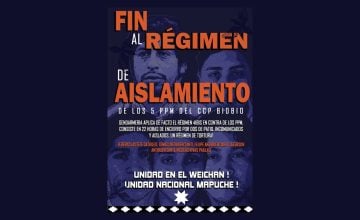

Amid the constant delays, the Mapuche political prisoners staged two hunger strikes to demand minimal guarantees in the process. These mobilizations, despite opposition from the plaintiffs and the Gendarmerie, resulted in recognition of their right to be tried in person and within a reasonable timeframe. However, in practice, the trial has continued to be postponed time and again.

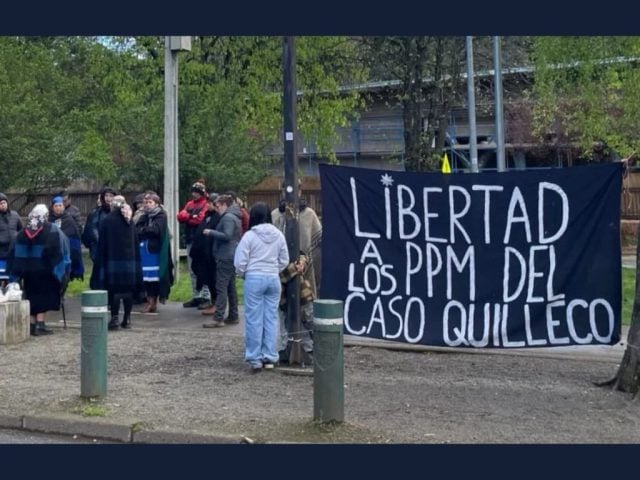

The oral trial was scheduled to occur on November 28, 2025, at the Oral Criminal Court in Los Ángeles and was anticipated to last several weeks, with expert testimony from BIPE, police, and protected witnesses linked to forestry companies. On that same day, Mapuche communities called for support during the trial and denounced the pressure exerted by the forestry sector in the criminal prosecution.

However, just hours before the start, the hearing was postponed again, generating outrage among communities, families, and the legal team. For attorney Rodrigo Pizarro, this new delay constitutes an affront to the Mapuche People and highlights the discriminatory treatment within a judicial system that keeps five defendants imprisoned without a verdict for over two years.

For the Mapuche Nation and various organizations, the Quilleco Case represents a critical moment in the conflict among communities, the State, and the forestry sector, marked by what they characterize as political criminalization, the use of protected witnesses, and prolonged preventive detention. In this context, major demands include the release of Mapuche political prisoners, the end of anonymous witnesses, the non-application of the Anti-Terrorism Law, the respect for judicial and cultural rights, and ongoing support for families and communities engaged in resistance.

Dismissal of Marilao: A Recent Example of Judicial Collapse and Inconsistencies

The situation faced by the five defendants in the Quilleco Case does not occur in a vacuum. In the same jurisdiction, the Oral Criminal Court of Los Ángeles recently ordered the definitive dismissal and immediate release of Mapuche community member José Luis Marilao in the so-called «Fundo Punta Arenas» case, reigniting criticisms of the functioning of the judicial system in cases involving Mapuche community members.

The «Fundo Punta Arenas» case was marked from the outset by serious irregularities. Marilao was part of a group of four community members who were prosecuted and acquitted four times, always due to insufficient evidence presented by the Public Ministry. Despite this, the prosecution continued with new cases and precautionary measures that his family and defenders deemed arbitrary.

Diverse organizations reported indications of setup in this process, including the use of manipulated evidence and the persistence of maintaining Marilao in preventive detention without solid evidentiary basis. The defenses argued that the prosecution sought to insist on his incarceration even after the judiciary indicated the fragility of the case.

The recent dismissal closed one of the most questioned cases in the region, characterized by severe judicial overreach and evidentiary shortcomings. For communities and organizations associated with the Mapuche, this ruling confirms a troubling pattern in the criminal prosecution of community members where irregularities, unjustified delays, and the abuse of preventive detention recur.

In this context, the Quilleco Case is viewed as an extension of the same structural problem. The constant postponements, lack of available judges, more than two years of preventive detention, and accusations based on protected witnesses reinforce, according to defenders and communities, the notion of discriminatory treatment within the judicial system. For the defendants’ environment, the events in «Fundo Punta Arenas» serve not only as a recent precedent but also as a reminder that procedural violations in Mapuche cases are not isolated incidents but part of a continuing pattern.

The patterns evident in these cases raise questions about the actual capacity of the Judiciary to guarantee due process to Mapuche defendants. They also reaffirm the question: Does the Chilean State have the real capacity—and willingness—to fairly judge Mapuche political prisoners in accordance with the law?