Chile’s Supreme Court upheld the convictions of three retired Army officers for their roles in the aggravated kidnapping of 35 people in the city of Iquique and the town of Pisagua during various periods between 1973 and 1974.

In a unanimous decision (case file 53.180-2024), the Second Chamber of the high court—composed of Justice Manuel Antonio Valderrama, Justices María Teresa Letelier and María Soledad Melo, and attorneys (i) Juan Carlos Ferrada and Raúl Fuentes—found no error in the challenged ruling by the La Serena Court of Appeals, which sentenced Conrado Vicente García Giaier and Pedro Santiago Collado Martí to life imprisonment, and imposed a 20-year effective prison term on Arturo Alberto Contador Rosales, all as authors of the crimes.

In the first-instance judgment, visiting minister for Human Rights cases in the jurisdictions of Arica, Iquique, Antofagasta, Copiapó, and La Serena, Vicente Hormazábal Abarzúa, established the following facts:

‘a) From September 11, 1973 onward, numerous residents of Iquique—supporters, sympathizers, or members of the Communist, Socialist, or MAPU parties—were detained. In some instances they were accused of specific acts, such as organizing plans to poison the city’s water supply, attacking military barracks, belonging to paramilitary groups, kidnapping the children of service members, organizing, holding, or participating in clandestine meetings, stockpiling weapons, and attempting to seize basic public services, communications, and the port by force, among others. In most cases there were no formal charges beyond their sympathy with, proximity to, or membership in a left-wing political party that was then legally constituted and operating within the country’s institutional framework, or for being members of the Movimiento de Izquierda Revolucionaria (MIR).

b) All of those people—men and women of varying ages, from adolescents to middle-aged adults—under orders from General Ernesto Carlos Joaquín Forestier Haensgen (deceased), commander in chief of the Army’s Sixth Division and head of the State-of-Siege Zone in Tarapacá Province, were taken—men to the Sixth Division or the First Carabineros Precinct of Iquique—and invariably ended up at the Telecommunications Regiment of the time. There, they were placed in areas akin to yards and later separated by political affiliation or other reasons into containers, “chancheras” (pigsties where the military raised hogs), or an “oasis” area (a section with vegetation).

All detainees were asked for their personal details by Army personnel; a portion of them were interrogated on a second floor—presumably in the infirmary building—and many were tortured in various ways and with differing intensity, depending on the political importance ascribed to them by the military regime. Based on that same perceived political significance, they were then sent to Pisagua either immediately or after several days, typically by truck at early or late hours, guarded by personnel from the same branch of the Armed Forces.

c) In the case of women, their processing ran through the Logistics Battalion under Army control. They were then transferred to the Buen Pastor facility, overseen by nuns, where they were held alongside women convicted of common crimes, and subsequently sent to Pisagua. There, they were kept detained on the second floor of a theater under armed guard.

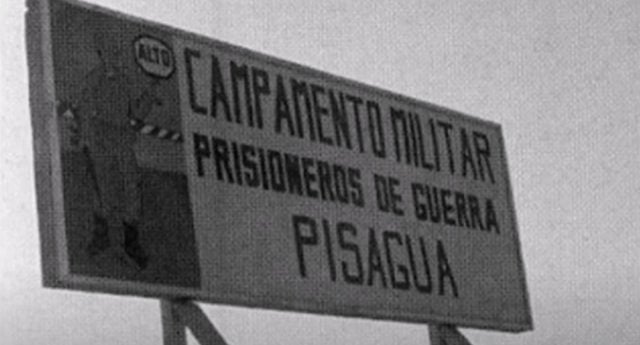

d) The Pisagua Prisoners’ Camp was directed by Lieutenant Colonel Ramón Caupolicán Larraín Larraín (deceased), comptroller and commander of the Prisoners of War Camp and Military Garrison of Pisagua, who in turn received direct and peremptory orders from Ernesto Carlos Joaquín Forestier Haensgen.

The camp’s guards consisted of a contingent led by a captain, assisted by two or more lower-ranking officers—lieutenants or sub-lieutenants—and the corresponding NCO troops. Larraín oversaw the intake of detainees and, under his command—directly or delegated to the officers guarding the camp—sessions were carried out that victims called “ablandamientos generales,” consisting of all manner of blows to different parts of the body, with greater or lesser force. These “tasks” were executed by the duty contingent, with certain Carabineros or Army officers standing out, and the officers in charge of the guard repeatedly taking on those roles.

e) When the camp began operating, prisoners were assigned—based on perceived political importance or party—across different floors of the jail. The lowest level, dubbed the “catacombs,” consisted of cells in the worst condition and with the greatest overcrowding.

Over time, the prisoners themselves were forced to build additional pavilions to house more people—structures that were never completed. During that period, some inmates were granted limited privileges owing to their skills, chiefly manual trades, such as cooks, shellfish-diver foragers, furniture makers, or orderlies. Even so, they could not help noticing the physical effects that the beatings caused their companions. In the same period, a group of journalists visited under the guise of the International Committee of the Red Cross and—despite the cosmetic sprucing-up ordered by Commander Larraín—managed to film and inform the world of the camp’s existence; the video was turned into a document that remains on file.

f) Only a portion of those detained in Pisagua were subjected to courts-martial, which were held at the local school. There were councils for the Socialist Party, the Communist Party, or involving multiple parties, composed of various officers specially convened for the purpose. Mario Sergio Acuña Riquelme (deceased) served as prosecutor, and the sentences determined by the council were ratified by Ramón Larraín Larraín and Carlos Forestier Haensgen, interchangeably.

A large percentage of prisoners were condemned informally; that is, without a written sentence—or at least without receiving one—often condemned solely on the basis of confessions obtained through torture, and required to travel by their own means to the places where the penalties were to be served, remaining imprisoned or relegated until completion, reduction of the sanction, or commutation through exile.

g) Alongside the “collective softening” sessions, there were individual interrogations aimed at obtaining the aforementioned confessions, carried out by a specific and permanent group under the command of prosecutor Mario Acuña Riquelme and composed, among others, of Roberto Fuentes Zambrano (deceased), René Valdivia Castro (deceased), Miguel Chile Aguirre Álvarez (deceased), and Blas Daniel Barraza Quinteros (deceased). On some occasions they interacted with the officers in charge of guarding the Prisoners’ Camp, and they applied torments that left victims with physical and/or psychological aftereffects, as documented by expert examinations conducted in accordance with the Istanbul Protocol by the Legal Medical Service.

h) This interrogation team regularly traveled from Iquique to Pisagua in a small aircraft piloted by Army officer Carlos Teodoro de la Barra Daniels (deceased). The reason this group did not remain permanently in Pisagua was that they executed the same practices against detainees at the Telecommunications Regiment, where they were under the command of Pedro Santiago Collado Martí who, by his own account, led the Military Intelligence Service—made up of soldiers and Carabineros—and had a friendship with prosecutor Mario Acuña Riquelme, holding meetings he called “colloquial” at least once a week.

i) In general terms, the tortures included blows to the body with rifle butts, hands, and feet; forcing detainees to lie naked or semi-naked on the floor while guards walked over them; sleep deprivation; exposure to the sun for hours and to the nighttime cold without clothing; climbing up and down hills using toe-and-elbow exercises; throwing them inside drums down slopes; electric shocks to specific parts of the body; dunking the head in water (“submarine”); blows to the ears (“telephone”); mock firing squads; interrogations in which a firearm was left at their side; suspension by the limbs to stretch the body for prolonged periods; rape; sexual abuse; keeping them on scant food rations; and the constant threat that they or their relatives would be executed, among others’.

El Ciudadano