Original article: «Neoliberalismo a la chilena, medio siglo de modelo, tensiones y futuro»: Entrevista con Andrés Solimano y Gabriela Zapata

In Chile, few words divide opinion as much as «neoliberalism,» yet few so accurately describe the economic framework that has shaped the country over the past 50 years.

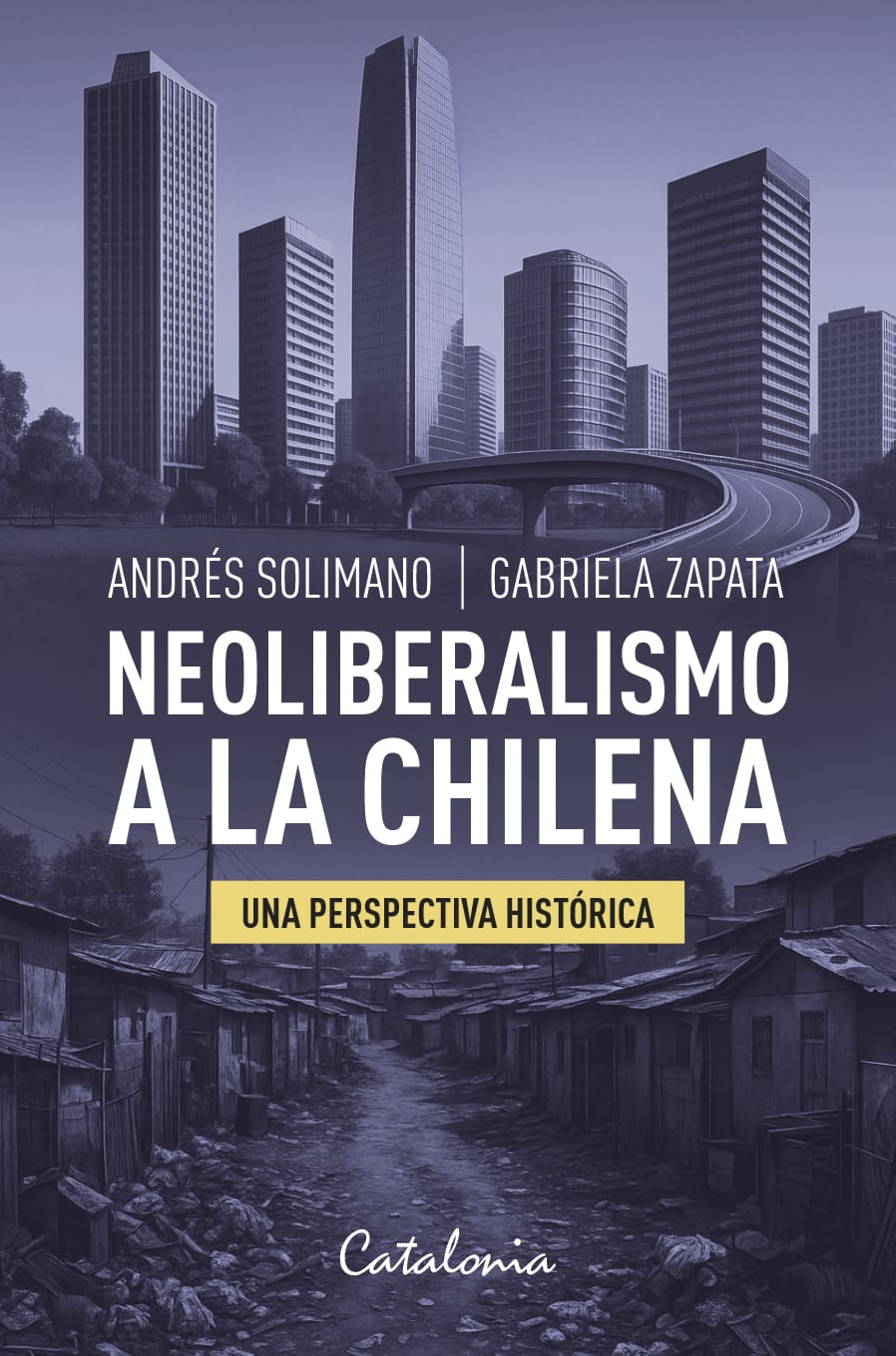

In «Neoliberalism in Chile» (Editorial Catalonia), economists Andrés Solimano and Gabriela Zapata propose a counter-narrative to the typical discourse: they aim to lower the temperature, shine a light on, and examine with evidence a model that is so entrenched it often evades critical judgment.

The book stems from an academic essay by the authors published by Cambridge University and the United Nations University’s World Institute for Development Economics Research.

Translated into Spanish and adapted for a broader audience, the work reconstructs half a century of radical transformations in the country, from the economic laboratory of the dictatorship to its continuation, with nuances, during democracy.

The authors rigorously explore the processes of privatization, deregulation, inflation, employment, education, health, housing, and pensions, among other topics. The analysis presents data illustrating where the model has succeeded and where it has faltered, suggesting that the next cycle of development in Chile must balance growth, social cohesion, and environmental care.

We spoke with both authors to delve into the central questions raised in their book: How did the neoliberal model become normalized in Chile? What were its successes, and where did its limitations begin to surface? What roles did inequality, economic power, and the weaknesses of public education play in the persistence of this development pattern?

Most importantly, what must change to usher in a new cycle of growth, social cohesion, and environmental sustainability?

Throughout the interview, Solimano and Zapata review five decades of institutional decisions, political tensions, and social outcomes; explain why the transition of the 1990s definitively consolidated the model; discuss the «fatigue» of growth overly reliant on natural resources; and propose concrete pathways to rebalance the role of the state, social protection, and productive structure. Their responses—meticulous, historical, and devoid of caricature—provide tools to comprehend not only the recent past but also the tangible possibilities for transformation in the future Chile.

–The term «neoliberalism» often generates more noise than analysis. What was the biggest methodological challenge in presenting a historical and empirical perspective rather than an ideological one?

The term neoliberalism is used in economic and social science literature to describe a new economic liberalism, distinct from that of the 19th century, emerging with the Mont Pelerin Society and other conservative groups from the 1930s and 1940s.

As early as the mid-20th century, Milton Friedman used this term, and Hayek also subscribed to it. In our book, we employ this concept and give it a historical perspective. Our aim was to reconstruct, using evidence, what reforms were truly implemented, how they functioned, and what their effects were.

We had to work with archives, administrative data, policy documents, and international comparisons to showcase the functioning of the Chilean model, without caricatures. That rigor was essential, as the Chilean case cannot be understood as an abstract debate but as a concrete sequence of institutional decisions made over 50 years, starting in the mid-1970s under Pinochet.

–You argue that the Chilean model has become «naturalized» in the culture. What concrete expressions did you find in the labor market, public policies, and citizen perceptions?

This naturalization appears in various layers of daily life. In the labor market, the idea that social protection is an individual responsibility has taken hold: saving in pension funds, acquiring training, going into debt for education or health.

In public policies, it has become almost obvious that the state should operate through demand subsidies, while direct provision has been relegated.

Furthermore, there is a strong notion among citizens that individuals must «manage on their own,» that going into debt is normal, and the market is the legitimate mechanism for accessing essential goods.

An important consequence has been the promotion of individualism and materialism, normalizing the payment for everything and extolling profit motives in areas that were historically organized differently: education, health, pensions, prisons, etc. This set of beliefs has created a new «common sense» (neoliberal) allowing the privatizing model to persist beyond governments, even when its outcomes reveal clear limits, especially in terms of inequality, productivity, and social mobility.

–In reconstructing half a century of transformations, what do you consider the most decisive turning point for solidifying the current economic model?

The pivotal moment was, probably, the institutionalization of the model during the 1990s. The democratic transition chose to maintain fundamental pillars inherited from the previous period: trade openness, the pension system, targeted social spending, privatized provision of social services, the autonomy of the Central Bank, and demand subsidies.

This continuity, rather than any specific reform, converted the model into the stable and enduring framework of the Chilean economy. It was at this point that it ceased to be an experiment and became an established structure, with persistent effects on inequality, productivity, and the understanding of the state’s role.

The ongoing existence of the 1980 Constitution has also hindered substantive reforms of the model left by Pinochet. Continuing with the same constitution from the authoritarian period (with some reforms) 35 years after the restoration of democracy makes Chile an anomaly in post-authoritarian transitions worldwide. It starkly contrasts with Spain post-Franco, Brazil after the military regime, South Africa post-apartheid, and other cases where new constitutions and institutions aligning with their new democratic realities were established. This has not occurred in Chile.

-Privatization, deregulation, and trade openness defined the neoliberal cycle. Where do you see its main achievements and signs of «fatigue»?

The immediate achievements were clear: macroeconomic stability, inflation control (which was a slow and socially costly process), modernization of sectors, and accelerated growth in the 1990s and 2000s.

The “fatigue” appears in areas for which the model was never well-designed and are simply inherent to it: social inequality in income, wealth, and opportunities, social protection, and diminished upward mobility due to the planned deterioration of public education, deindustrialization, environmental degradation, and over-exploitation of natural resources. It is not that the model was weak in these dimensions; rather, the market does not produce equity because its logic revolves around efficiency and the allocation of goods based on purchasing power.

This is why, when the supply of essential goods depends mainly on the market, it is expected that inequality will persist and that many people’s basic living conditions will be contingent on their income rather than guaranteed social rights.

–What lessons does the Chilean experience provide regarding the limits of growth based on natural resources? What alternatives do you envision for the future?

One of the key lessons reinforced by the United Nations University (Tokyo) and the World Institute for Development Economics Research (Helsinki), with whom we collaborated in preparing this book, is that inequality is not merely economic; it also generates a functional power structure and is reinforced by it.

When wealth is highly concentrated, political influence also concentrates, making it extremely difficult to promote structural reforms, even when there is broad citizen consensus on their necessity. Dominant elites will block changes that are not favorable to their interests and exert significant influence over the political system and dominate communication systems.

Additionally, the Chilean case shows that it is possible to grow for decades without generating significant social mobility. Public education was dismantled decades ago and has progressively deteriorated; despite the massification of higher education, the quality of education remains a critical issue, and many professional degrees for which students pay—often at considerable cost and debt—do not translate into quality, stable jobs.

This is compounded by stagnating productivity, often attributed to workers, when in reality the issue is structural: even if our graduates had top-notch skills, in what high-productivity sectors would they work? Chile has not developed complex industries capable of absorbing skilled labor or driving innovation, and without that productive transition, the country remains trapped between natural resources and low-productivity work.

The alternative requires simultaneous progress on at least three fronts:

- Strengthening and modernizing public education;

- Promoting industrial sectors with higher added value and technological complexity;

- Building a state capable of coordinating the transition to a different education and productive system.

Without moving these pieces together, we will once again collide with the same limits.

-Sectors such as health, education, housing, and pensions were designed as «markets.» Which sector requires the most urgent reform today?

Today, the urgency is not concentrated in a single sector but rather reflects the structural fragility experienced by large segments of the low-income population and middle classes. Although pensions have improved somewhat after recent reforms, many people remain trapped in a cycle of low wages, informality, precarious micro-enterprises, and a healthcare system that does not always respond in a timely manner.

Higher education has become widespread, but without generating genuine social mobility: the quality of schooling remains unequal, and the value of academic credentials is highly segmented. Furthermore, students graduate burdened with substantial higher education debt.

If someone loses their job, the social protection system allows them to sustain themselves for just a few weeks. An unexpected illness, dismissal, or adverse family event can completely destabilize a household both economically and emotionally.

Thus, the urgency lies in strengthening social security, formal employment, and the high-quality public provision of services. It is not just about efficiency or equity: it is about restoring stability to lives that are currently perpetually on the brink of falling into a chasm of poverty and debt.

–From a comparative perspective, in what ways does Chile remain exceptional, and in what ways does it increasingly resemble Latin America?

Chile continues to be near the top regionally in per capita income and possesses significant macroeconomic frameworks, fiscal rules, and institutional stability by regional standards. However, it also mirrors the rest of Latin America in terms of persistent inequality, low social mobility, labor informality, and socio-environmental tensions.

The myth of Chile as a «special case» is less sustainable today than it was 20 years ago, especially due to productivity stagnation and the lack of complex industrial sectors characteristic of developed countries.

-Looking towards a new election cycle, which inertia of the model will survive and what real margins for reorientation exist?

Certain deeper traits of the model—trade openness, autonomy of the Central Bank, and an institutional design favoring private action (biased towards large companies)—will likely survive any coalition because they are embedded in the economic architecture.

The margin for reorientation lies in labor policies (wages, negotiation capacity, working hours), strengthening the public provision of collective goods and social services, regulating concentrated markets, and expanding social safety nets.

However, a critical point must be acknowledged: inequality also shapes the capacity to implement reforms. When economic power is highly concentrated, the political space narrows. With a simple majority, it is possible to improve regulations and expand social rights; however, structural reforms—taxation, pensions, and health systems—require broad agreements, particularly because they affect concentrated interests.

-If «de-neoliberalizing» meant only three practical and measurable changes, what would they be? What political costs would you accept?

Three changes with real impact would be:

- Expanding direct and free public provision in health, education, and care, reducing reliance on out-of-pocket payments and indebtedness.

- Strengthening regulation and competition in highly concentrated sectors, from pensions to digital markets. Effective market and ownership deconcentration is needed.

- Increasing progressive tax collection to finance public goods and reduce social vulnerability.

Each of these carries some political cost because they involve redistributing power and income. However, the Chilean case illustrates that without addressing the persistence of inequality and its effect on politics, reforms become nearly impossible. Accepting that conflict is part of the path toward more inclusive development.

Ultimately, it is essential that the population becomes aware of its rights and acts in an organized manner to preserve and expand those rights; it would be risky for the working class to rely solely on parliamentary representatives, who often have their own agendas and depend on private funding for their campaigns and re-elections.

El Ciudadano