The latest report from the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) is not encouraging. At the end of 2019, there were 687.8 million undernourished people in the world (8.9% of the population). The projection for 2030 is 841.4 million (9.8%) or one in 10 inhabitants. A real food crisis.

In the case of Latin America and the Caribbean, there are 47.7 million undernourished people (7.4%). However, the estimate for 2030 is 69.9 million (9.5%). But what is the most worrisome thing of these calculations? That the FAO still does not foresee the impact that the coronavirus will leave behind. «We cannot project the numbers because we do not know how long this health crisis will last«, explained Julio Berdegué, FAO regional representative, in an interview with CNN.

In this regard, the Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC) estimates that the pandemic will lead 28 million people into extreme poverty. This regional increase of 40% will undoubtedly have a great impact on food security.

And, in the midst of this global health crisis, what hope is there for Venezuela? It is a people besieged by sanctions and a hermetic economic, commercial and financial blockade imposed by the United States Government.

‘And now, who can help us?’

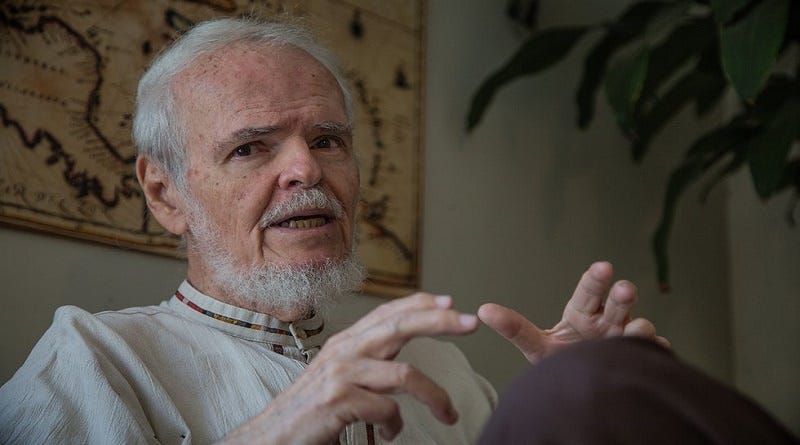

In an exclusive interview, Luis Britto García, a Venezuelan lawyer, essayist and university professor of the History of Political Thought, recalled three historical antecedents of countries that have experienced similar situations.

«The Soviet Union and China were cornered for almost the entire last century by blockades, sanctions and diplomatic sieges. Even so, they developed powerful economies: the Soviet’s economy was the second in the world, while China is the first today», he said.

The third case that he highlighted is Cuba. This country, after almost 60 years of blockade, «has a high level of self-sufficiency» in production and food. So, considering those precedents, how could Venezuela survive even when cornered by sanctions?

«Dedicating ourselves to development and internal production. Discarding, once and for all, the illusion that the transnationals or the bourgeoisie will finally come to save us«, emphasized Britto García.

In that sense, he underlined the need to learn from other experiences, including North Korea and Vietnam. «In these countries, the large land estates were eliminated and the agri-food production was socialized. Thus, they managed to satisfy their demand, despite terrible situations of blockade and military aggressions», he said.

The impassive private sector

Britto García warned that the health crisis intensifies the vulnerability and inequality of the food systems. This situation could provoke that 83 to 132 million people starve by the end of the year.

His estimate derives from the report «The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World«. The text was prepared by FAO, the World Health Organization, the Fund for Agricultural Development, the UN Children’s Fund (UNICEF) and the Food for the World Program.

“A dozen transnationals and 36 interconnected subsidiaries dominate food production and marketing (…) They manage 95% of the system in the United States, Europe, the 54 countries of the Commonwealth of Nations and Latin America, especially Argentina and Brazil. Five billion people depend on their crops» or 65% of the world’s population, he explained.

He also stated that this «colossal oligopoly» has depressed food production in the rest of the world. «It has initiated the elimination of protectionist policies and subsidies, the suspension of financing and large agricultural projects, dumping (sale at a loss) and dominance over seeds and fertilizers».

Can the private sector end the crisis?

«In simple terms – he continued – the private sector is not interested in, nor is it convenient for them, to prevent or address a food crisis. They are only interested in their own benefits, even if they are achieved at the cost of human suffering».

“The United States is an example of what happens when the private sector dominates the State: in order not to diminish corporate profits, they denied that there was a pandemic. Later, its importance was downplayed by treating it like a seasonal flu. Then, they avoided declaring a national quarantine», he recalled.

The result: almost 28 million infections, about 500 thousand deaths and the highest unemployment rate in its history. Furthermore, (former) President Donald Trump lost re-election and left the White House through the back door.

State, workers and society

In 2004, the FAO admitted that neoliberal policies, the free market and the adjustments dictated by the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund and the World Trade Organization make it impossible for countries to ensure the human right to food.

In this sense, Britto García added: «Food is not a business. It is a fundamental matter of life and death for humanity. Governments —including Venezuela— must assume social control of agricultural and livestock production. Also, as in the case of health, prioritize the interests of the population over capital».

In that same sense, he reaffirmed that the pandemic has been neutralized, or at least contained, in countries where the State exercises some control over the economy. The most palpable examples are China and Cuba.

Meanwhile, the virus unleashed itself in countries with neoliberal systems, such as the United States, Brazil, Peru, Chile, Ecuador and Colombia. Their governments promote the concentration of ownership of farms. Also the indiscriminate use of transgenics and monopolies and oligopolies in the distribution of food.

«The State, in coordination with workers and society, must exercise effective control against these market distortions», emphasized Britto García. In addition, it must understand that agroindustrial production is based on a very poorly paid and vulnerable sector. Therefore – he explains – it is to them that it (The State) must offer financing, subsidies and sanitary facilities. Why? Because they are the ones who can overcome this latent food crisis.

In this sense, he urged that attention must be given to small and medium producers, as they will receive a strong impact from this situation. «The massive bankruptcy of these small businesses will always benefit the large private capital, which will be able to redistribute their assets and clients», he said.

Food crisis in a mono-productive country?

Additionally, Britto García called on the Government to review production rates and distribution and cost chains to avoid a food crisis. He cited a work by the economist Pasqualina Curcio, which revealed that, in general terms, since the last decades of the last century, Venezuela produces 88% of the food it consumes.

“Historically, according to the National Institute of Nutrition, 88% of the food we consume is produced in Venezuela. The national production of eggs is 99%, of roots and tubers 99%, of vegetables 97%, fruits 98%, milk and cheese 98%, meats 92%, fish and seafood 70%, cereals 63%. What we import is wheat, soybeans and part of the corn, also a good part of the legumes: 91%. We invite you to check out your market list. Where do you think the bananas, coriander, yucca, squash, bananas, oranges, tomatoes, red peppers, eggs, meats, milk, chicken, cheese, ham, onion, rice, pasta, cornmeal, and the bread you eat were produced?».

Pasqualina Curcio

For this reason, Britto García concluded: “when the economic war flared up, there were supposed ‘shortages’ of processed or easily hoarded or refrigerated foods, such as flour, meats and eggs. But tomatoes, potatoes, onions and fruits were sold unlimitedly on the streets».

Perhaps the answer to this dilemma has been expressed by Julio Berdegué, FAO regional representative: “Although Latin America and the Caribbean has a great production of food, vegetables, dairy, meat and fish; It is the region where it is more expensive to eat healthy: 3.98 dollars per day (…) Even simpler: having a sugary drink is cheaper than drinking milk».