By Lucía Sepúlveda Ruiz.-

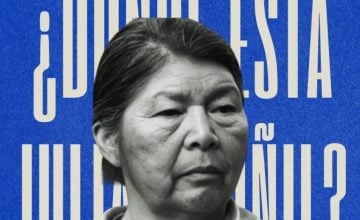

“They burned her,” Juan Carlos Morstadt allegedly told his father by phone, referring to Mapuche leader Julia Chuñil Catricura, who disappeared from the disputed ancestral territory of Los Laureles, in the commune of Máfil, Los Ríos Region.

The stark revelation from a court-authorized phone intercept was presented in Santiago at CODEPU by the family’s defense attorneys, Male Santana and Karina Riquelme. Ten days ago, prosecutors cut off all of their access to the case—revoking their accreditation and ignoring their repeated appeals to date. Left without any official information, they denounced the move as a serious violation of the IACHR’s precautionary measures.

Alongside the legal team were Pablo San Martín, Julia’s eldest son; Juana Aguilera of the Ethics Commission Against Torture; and Rodrigo Bustos of Amnesty International, who reiterated the need to safeguard due process and guarantee access to justice. As of September 30, the family has received steadfast support and solidarity from the Espacio Día a Día por Julia Chuñil and from grassroots collectives across Chile, who have been pressing the State with the question “Where is Julia Chuñil?” while demanding truth, justice, and accountability for her disappearance.

Morstadt is an indicted suspect in the case. He refuses to answer questions, but thousands of voices—hoarse with grief and shock—are now demanding answers. Mr. Morstadt, tell us: who burned Julia Chuñil? Who gave the order?

Jaime Calfil, the current prosecutor (pictured in the cover photo)—whom the legal team had asked not to be assigned to the case due to ideological bias—has chosen, instead of indicting the businessman, to widen the pool of suspects to include Julia Chuñil’s three children, along with other relatives and friends.

Despite this clear evidence, and another phone intercept that links Morstadt to unauthorized firearms, the Prosecutor’s Office continues to amass elements for a narrative that diverts attention from the person presented as chiefly responsible: an agroforestry businessman with ties to political and financial power networks in the Los Ríos Region.

“If anything happens to me, you already know who it was.” Those close to Julia recall her ominous warning after a series of threats that preceded her disappearance.

The defendant also owes the State more than 1,000 million pesos to Conadi—debt he has failed to pay—even after the agency returned to him, without charge, the 900 hectares at the center of the dispute.

Mistake—or a strategic leak?

For several hours a few days ago, the website of the Ministry of Justice and/or the Prosecutor’s Office published—whether by incomprehensible error or by design—reserved memorandum No. 1849 from Prosecutor Calfil to the Guarantee Judge of Los Lagos, requesting “intrusive measures” (telephone interceptions) that were not added to the official case file.

The background information we summarize below—as well as Morstadt’s statement about Julia Chuñil’s fate—appears in that memo. Days before another anniversary of her disappearance, these materials could once again be deployed by pro-establishment media seeking to delegitimize the fight for truth and justice for Julia by shifting blame onto her family.

In his filing, the slapdash prosecutor Calfil tells the judge he has three confidential (secret) witnesses, without providing any substantive details. They are likely Carabineros, as one of them claims to have heard one of the audio recordings referenced in the narrative.

These secret witnesses are his primary source for naming suspects. The list includes Pablo San Martín, allegedly because his mother sold him a plot of land days before she vanished. Based on remarks attributed to a minor by one of the secret witnesses, Julia’s daughter, Jeanette Troncoso, is also presented as a suspect.

Javier and Andalién—the other two sons—likewise appear on the list for purported contradictions on the first day of the search. A secret witness claims to have seen the three siblings burning their mother’s clothes in a gasoline drum outside Julia’s house.

To secure the judge’s authorization, Prosecutor Calfil also cited the supposed discovery of blood traces belonging to the sons, Javier and Andalién, inside the recovered house and on a splinter from the cart—findings that were never entered as evidence in the investigative file. He cites LABOCAR analyses, an office reportedly under the command of noncommissioned officer José Arriagada, who has a record of failures and bad practices in a Biobío case involving a minor and was removed from that matter. In this case, the attorneys say he led geo-radar searches that focused exclusively on the family.

Displaying a total lack of familiarity with enforced-disappearance protocols, Prosecutor Calfil interpreted the phrase “no body, no crime” as self-incrimination by another family member—whom he accuses of “handling confidential information.” Yet that phrase has long been used by relatives searching for a disappeared loved one. The posture reveals a dismissive underestimation of the knowledge families acquire amid their pain and desperation.

This is the same prosecutor who never opened proceedings in the corporate femicide of Macarena Valdés. We recall that Rubén Collío publicly denounced Prosecutor Calfil in 2019 for handing the investigative file on Macarena’s death to employees of RP Global. Those employees were the main suspects, having previously harassed and threatened the young mother of four, a defender of her territory.

Later, amid a revolving door of prosecutors—much as we see now—the investigation lost the report from the independent autopsy, which concluded that Macarena had been killed before being hanged in a staged suicide.

With the 11-month mark of the disappearance of Julia Chuñil—defender of forests and waters, mother, and grandmother—just days away, impunity and staging go hand in hand, while class-based justice ignores international warnings about its corrupt conduct. In August, the government told the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights and civil society organizations that it was redoubling efforts in the case and keeping the family informed, as requested.

Keeping Calfil in charge of the case is, by any measure, untenable.

By Lucía Sepúlveda Ruiz.-

Read more:

El Ciudadano